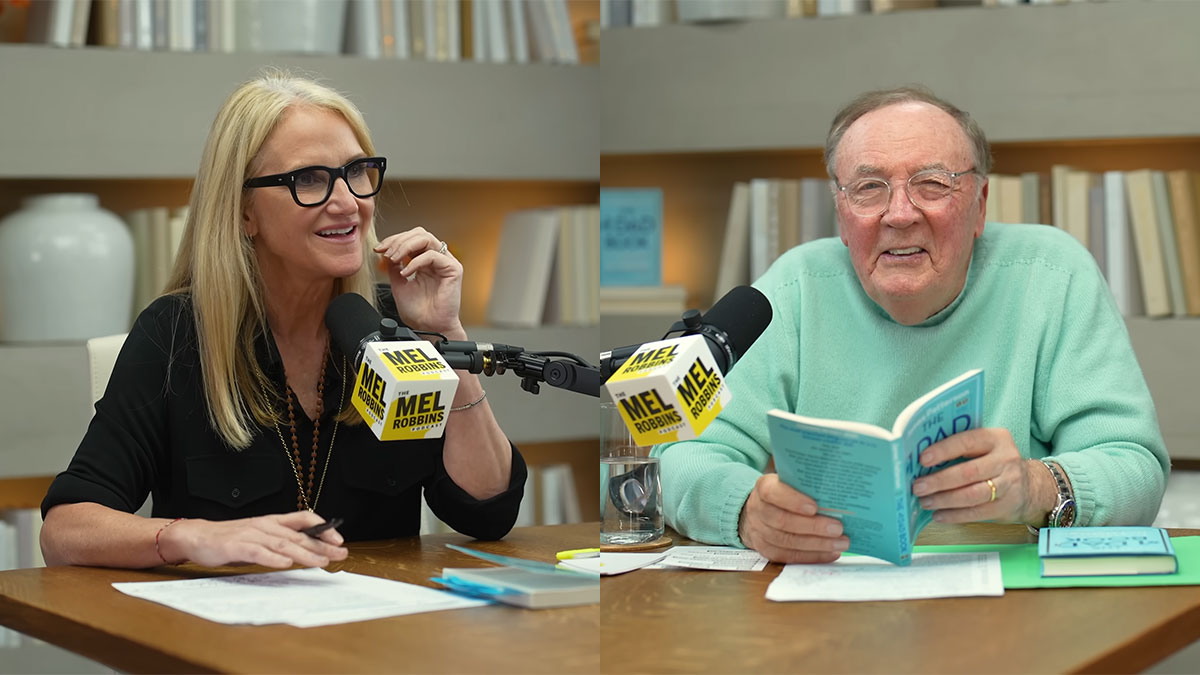

Episode: 311

You Learn This Too Late: Understanding This Will Change the Way You Look at Your Relationships

with Dr. Aliza Pressman, PhD

Reveal the hidden parenting patterns shaping every relationship you have—and learn how to transform them for the better.

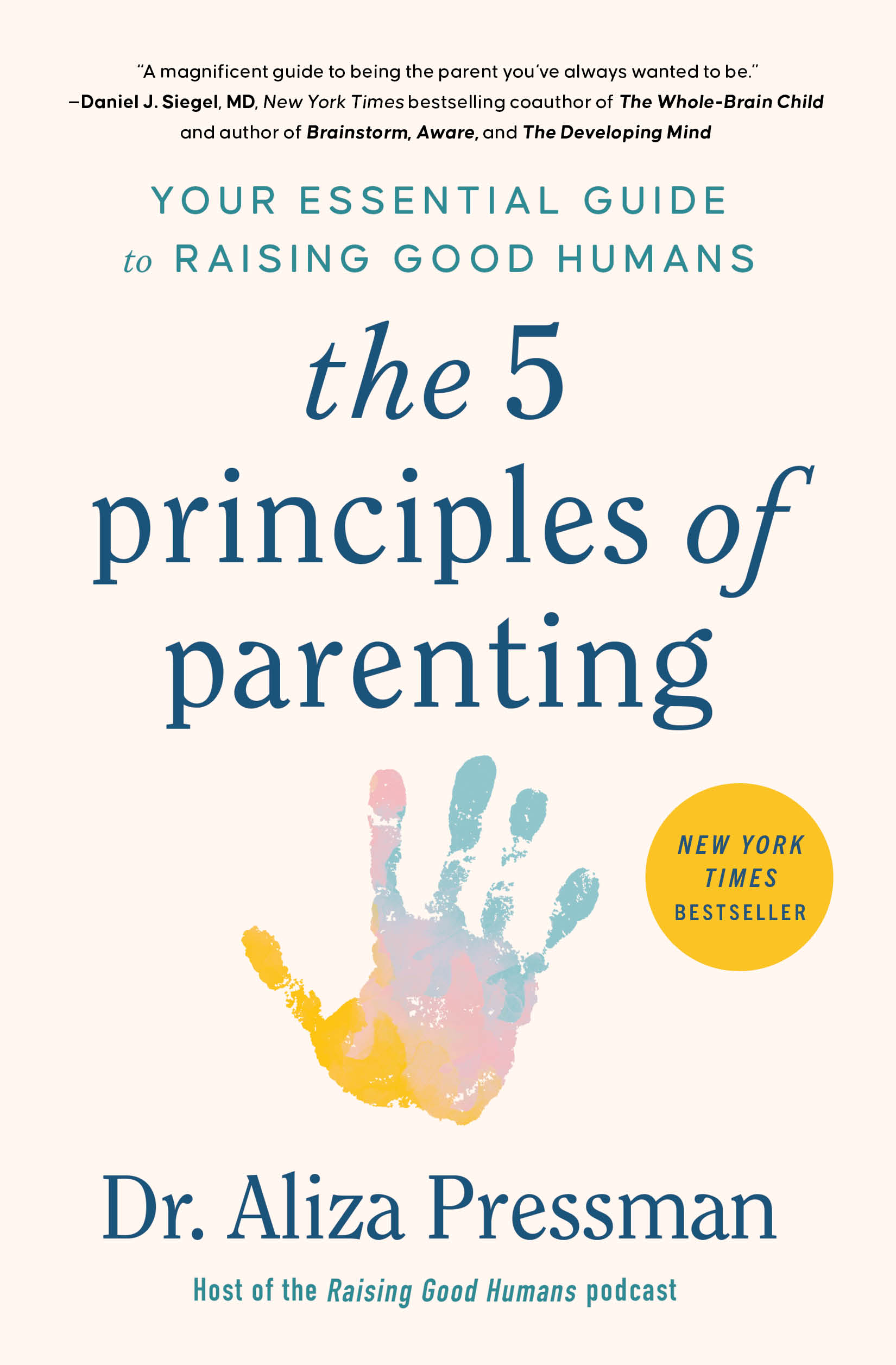

Dr. Aliza Pressman, a leading developmental psychologist and bestselling author of The 5 Principles of Parenting, reveals the hidden patterns from your own childhood that shape how you parent, love, and connect.

She shares five principles that will change how you parent forever, the single most important parenting strategy, and practical tools to repair mistakes, set boundaries, and raise resilient kids.

Even if you’re not a parent, these insights will help you become a better, healthier human.

The way we were parented, the way we grew, the way we became who we are—and the way we’re shaping others—sits at the center of everything.

Dr. Aliza Pressman, PhD

All Clips

Transcript

Aliza Pressman (00:00:00):

How we were parented, how we grew, how we came to be who we are and how we're growing others is kind of at the center of everything.

Mel Robbins (00:00:08):

What if you realize, my God, I've made a lot of mistakes. I was the parent that was indifferent or cold or distracted, or I had a lot of anger or I really screwed up the divorce. What would you tell somebody who feels like they're failing a parenting right now?

Aliza Pressman (00:00:23):

I would say,

Mel Robbins (00:00:25):

Wow. I think that's a hard pill for a lot of parents to swallow. Dr. Aliza Pressman, she's one of the world's most respected developmental psychologists. She has a New York Times bestselling book called The Five Principles of Parenting, your Essential Guide to Raising Good Humans. Today, Dr. Pressman is here to lay out the science behind the parenting mistakes most of us don't even realize we're making. Dr. Pressman is going to give you so much clarity about what you've experienced and more importantly, where you can go from here. What's the biggest myth parents believe about raising healthy, resilient kids? The biggest myth is that my mouth is hanging open, so I'm going to close it for a second. How does wanting the best for your kids cause anxiety? I should say this. Wow, I've never heard that before. After a divorce, how long should you wait before you introduce who you're dating to your kids?

Aliza Pressman (00:01:20):

The research suggests

Mel Robbins (00:01:21):

Dr. Pressman, what is the best parenting advice you've ever heard?

Mel Robbins (00:01:31):

Dr. Aliza Pressman, welcome to the Mel Robbins Podcast.

Aliza Pressman (00:01:35):

Thank you for having me.

Mel Robbins (00:01:36):

Thank you for coming to Boston. Thank you for being here. I was on the Today Show set and Hoda pulled me aside and said, my favorite parenting expert is Dr. Pressman. You have to get her on. And so I was like, Hoda, I'm getting her on. So welcome.

Aliza Pressman (00:01:53):

Thank you, Hoda. I love her.

Mel Robbins (00:01:56):

I do too. I do too. I'm really excited to learn from you and I'd love to start by having you tell the person who's listening right now, what they could experience in their life that could be different. If they take everything that you are about to teach us today and they apply it to their life, how could their life change?

Aliza Pressman (00:02:15):

How we were parented,

(00:02:17):

How we grew, how we came to be who we are and how we're growing others is kind of at the center of everything in my view. And I think that the science of the parent child relationship is extraordinary and it's inspiring and it is overwhelmingly easier to get it right. And I think that that is game changing, that there's stuff that you can do that will change the relationships in your life and that very easy to take on. There's so much information out there about how to do every single thing, but the science itself is quite generous with parents is such a beautiful experience. Once you really buy into that, you have actionable steps that you can take that can be game changing in your relationships, but they're not like this overwhelming unattainable goal.

Mel Robbins (00:03:15):

There were so much that you just said in that. I want to try to unpack a couple things that struck me. The first one was that you said that there's just simple things to do that the science supports that helps you get parenting largely right?

Aliza Pressman (00:03:31):

Yeah.

Mel Robbins (00:03:32):

I mean that's refreshing. I feel like I royally screwed up my children. I mean, I'm serious. I did not know the person that I am today at 56, not the person I was when I was 29, 30 and 34 when I had my kids

Aliza Pressman (00:03:49):

Of course.

Mel Robbins (00:03:50):

And so I think that is extremely positive and hopeful, and especially in today's world where everything feels very overwhelming to know that it's kind of simple and there are simple things you can do to get it largely right. I was also drawn in when you talked about the fact that we were all littles at once. We were all little kids. We've all been parented whether your opinion about how you were parented is that your parents did a great job or that your parents really screwed things up. We all have things that we wish we could change and what can you get out of this conversation and what you're about to teach us today If let's say you are in your early twenties or you're a teenager and you haven't had kids yet, or you don't know if you want to have kids or you didn't have kids.

Aliza Pressman (00:04:42):

I mean, the thing is is that if we can reflect on our experience being raised, our experience being parented and cared for and loved, we can then make choices about how we love and how we experience being loved by everyone in our lives. So it affects your romantic relationships. It affects how you connect with people who you choose to connect with, what feels like home to you.

(00:05:07):

We're all drawn to what feels like home. And if what feels like home was not an acceptable environment, that doesn't mean that we're going to be like, well, I don't want that experience again. Our whole nervous system wants that experience again, unless you're reflective about it and you make more intentional choices. So I think a 20 something year old thinking about this is exactly who can think about this and benefit. And then of course going into parenting and that whole transition to parenthood, so many of us are so afraid that we're going to relive the mistakes, that there's this generational trauma, that there are these cycles that we aren't going to break. But the thing is, the very fact that you're reflecting on that means you've already broken that cycle. And to me that is just so important. The work is this.

Mel Robbins (00:06:02):

My mouth is hanging open, so I'm going to close it for a second because you said the very fact that you may be worried about repeating the negative things that happened to you when you were a little kid or passing on the traumas from past generations. The fact that you're even reflecting on it shows that you've already broken it because why?

Aliza Pressman (00:06:30):

Because much of this challenge is just being aware of it. Once you're aware of something, you can't not change your behavior. You might not change it all the time. It might be just a tiny little change, but it's enough of a change that you've changed this cycle. There's a break in it. Now that doesn't mean that you're off the hook. We still have to work. We still have to be intentional. It's much easier to sort of forget things and not think about it and dissociate and just move along. But every time you take a pause to reflect, you are breaking that cycle and your behavior will change. It's a tweak. It's a tiny little thing. But what I think is so cool about this whole science is it doesn't require this gargantuan effort. It's like the small stuff and it really makes a difference.

Mel Robbins (00:07:29):

In your incredible book, the five Principles of Parenting, you do break down this whole huge body of science and research into five basic principles, and we're going to get into them in a deeper level. But can you just quickly break down what the five principles are?

Aliza Pressman (00:07:46):

Okay. It starts with relationship. By the way, I picked R words, not scientifically, just like it's hard enough to remember anything. So all R words, but all from the science relationship, which is this. It's just the connection between people. You might hear it as attunement, connection, anything that is attachment. All of those things are under this umbrella of relationship and relationship is kind of everything.

(00:08:15):

And then reflection, which we talked about. Reflection is I think an unsung hero of strong parenting because it feels light, it feels like, wait. So just thinking about something and really understanding it is moving the needle in my parenting. Yes, it is. And it allows you to pause, which brings you to regulation. So relationship, reflection, regulation that is sort of understanding that you have some control over your emotions, your thoughts, your actions, and and when you regulate, you also are, but that is co-regulating with your young little people in your life because we borrow the nervous systems of our caregivers.

(00:09:09):

And so if you're trying to develop a strong, robust nervous system, you need one around you that has capacity. So we've got relationship with reflection regulation, and then we need rules. And rules are really, really important for safety. So rules are boundaries and limits, and when you have boundaries and limits around the safety of yourself and the safety of others around you, so it's not just about protecting your child, but also they're going to be people in this world and they're moving through this world, how can they hold dear the emotional safety and physical safety of others while holding that for themselves? And then finally repair for when you screw it all up, which you will and we do over and over. And the research on repair is it's like the deepest breath of relief because you cannot have a close relationship without repair and you can't repair without screwing up.

Mel Robbins (00:10:08):

Now if you just heard those five principles of parenting and you reflect upon your own experience of being a child or being the child of a parent now regardless of how old you are, and you thought to yourself, I didn't check any of those boxes when I thought about my own experience, is there good news here?

Aliza Pressman (00:10:28):

There's such good news. Relationships are dynamic. Everything about this is dynamic. And so it's like a moving process. And we are born as parents when our children are born.

Mel Robbins (00:10:41):

Oh wait, we are born as parents when our children are born?

Aliza Pressman (00:10:45):

So of course we're new at it. Of course, we're messing up all the time because we're babies, we're baby parents. And so of course now when you have three young adults, you have a wisdom and a different parenting style because you've grown. And I think if our kids didn't see that, they would not have much hope that they get to make mistakes and grow and still be loved and be worthy. So I think if somebody said, I've done none of this, and by the way, I don't believe that because you're here, if you were like, ah, I want to listen to this episode, you're curious about this, which means there's so much hope. And also repair has no expiration date.

Mel Robbins (00:11:31):

So at any time you can use the principles to either make the relationship better in terms of with your own parents if they're still here or even if they've passed on. You can probably do the work to really understand and reflect and you can do the work with yourself to understand yourself better based on your experience of being parented by your folks. And if you are a parent, these are tools that you can use to be a better or more effective or what would the word be that you would use?

Aliza Pressman (00:12:04):

It's funny as you're saying that I think we use language around parenting that just pulls at a thread for people because it's so vulnerable and it's just like, so am I a better parent? Am I the best parent? Am I a perfect parent? I can't be any of those things. But I think it's like, is that word useful because do we want to be effective? Is that it? I mean, you do when you're trying to get stuff done.

Mel Robbins (00:12:29):

I've never thought about the actual adjective.

Aliza Pressman (00:12:32):

It's really hard to find one, but I just like to think we want to be good enough parents. That's good. Old Dr. Wincott said that a century ago, and I think we forgot that good enough is actually a good enough parent is the better parent.

(00:12:53):

The perfect parent is not helpful. It's hard, especially for women. You don't take something on as important as parenting without aiming for perfection. That would be counterintuitive, intuitive. What? Of course, I'm going to try to get this as right as possible, but the minute that you start to realize that that's not how humans operate, that being raised by someone perfect would put the child in a position to feel that that's attainable and that pressure is enormous and burdensome. So I think once you start to realize, oh, good enough is actually better for our children than perfect is, and it's more attainable for us so we can actually feel like we're the parents we want to be.

Mel Robbins (00:13:44):

And good enough is a term that's been around for a hundred years who coined this?

Aliza Pressman (00:13:48):

Donald Wincott.

Mel Robbins (00:13:49):

Okay.

Aliza Pressman (00:13:49):

And it was the good enough mother. And it sounds like I remember in graduate school being like, please, I'm not going to be a good enough mother. I think I can aim for a little bit higher. Yeah. If my

Mel Robbins (00:14:03):

Kids said, you were good enough. Hey, I was your mom. And I heard my kids going, ah, she was good enough. I mean, I'd be like, I know thanks a lot. Yeah, give me everything I gave you back. I was good enough.

Aliza Pressman (00:14:14):

Right? And I think if you translate how good it feels like the words good enough, the words like, okay, those don't translate to women very well. They feel so shitty. Yes, it feels like I failed. It feels like you failed. But once you realized how unburdened would you feel if you are worthy as a good enough mother instead of my mother was perfect, so I have to be perfect. That is such a burden. So it is necessary. If you really wanted to be the perfect, you would have to show mistakes over and over again to give that gift to your kids.

Mel Robbins (00:14:56):

What does that mean kind of in the research?

Aliza Pressman (00:14:59):

Okay, so in the research, it means you have a close connected relationship more often than not. So if more often than not you get relationship, reflection, regulation and rules going, you have all the rest of the time for repair. And I know this is going to sound hokey, but when you lift weights, you tear tiny muscles. In order to get stronger, you have to have tiny tears in that relationship. You have to have discord in order to have repair. There would be no opportunity for repair without it. And there is not a strong relationship without repair. So it's like a necessary part of this gig is to keep making mistakes.

Mel Robbins (00:15:44):

Well, that part I'm getting right consistently,

Aliza Pressman (00:15:48):

And I've got that down. My kids are like, you've got self-compassion and repair down, mom. We get it.

Mel Robbins (00:15:55):

So Dr. Pressman, what is the best parenting advice you've ever heard?

Aliza Pressman (00:16:02):

All feelings are welcome. All behaviors are not. That's it. If you were sitting there trying to figure out what to do, whether it's a tantrum from a toddler or whether or not your teenager just went way too far when they stole the car because they desperately wanted to go to the party, but you said no, whatever it is, the feelings that are underneath it are welcome. There's no wrong feelings. We are allowed and will feel how we feel. And it's really urgent that we know that we're allowed to have whatever feelings we have. But then we still get to say the behaviors are not all welcome. That is not okay to steal the car. It's okay to feel the feelings when you're tantruming, but it's not okay to clock your brother over the head.

(00:16:51):

When I think about all feelings are welcome. I think about when my daughter said to me, she was four years old, she came to me and she was so upset. She's 18 now, so I feel like it's fine for me to say this. She said, I think God's going to be really mad at me. Now, I don't know where she even got that whole thing, but I said, tell me why. And she said, because I had this horrible thought about my sister. And I was like, oh my gosh. So what did you do? And she said, I thought about it. And what she thought was just how terrible her sister was for breaking something. And I said to her, oh, sweetheart, you get to feel and think about anything. And we all have thoughts that we would not like other people to know and feelings that we would not like other people to know, but how you act is the thing that you have to pay attention to.

(00:17:47):

But just feeling those feelings, that is just part of being a person. And she was so relieved and it was so sad. A little 4-year-old didn't know that you're allowed to think I hate you. And so I just think about if you can grow up knowing that you're allowed to feel however you want to feel, how many times have you said, I should be grateful. I'm going to stop thinking this way, or I'm going to stop feeling this way. And you don't even give yourself the space to have all the feelings that people have. So I want every kid and every adult to be like, oh, all feelings are welcome. But then yeah, we don't get to do, just because we feel a certain way doesn't mean we get to act a certain way.

Mel Robbins (00:18:27):

Well, that's the first thing I'm taking away from this. No, I'm telling you that right now. Because I think that's something that every one of us needs to do for ourselves. And also in our adult relationship,

Aliza Pressman (00:18:37):

A hundred percent, none of this is really about parenting if we're honest.

Mel Robbins (00:18:41):

Well, I, I'm literally thinking about it in a work context that your feelings about things are welcome, but the behavior is not. I'm thinking about it with issues with parents or family members that are adults. Your feelings are welcome and they're valid. How you are acting is not, and it's such a helpful kind of hug with a punch. I kind of like it. But for me, because I just tend to be the kind of person that wants to make everybody feel like even with the let them theory, even with Let Them, I still feel drawn toward overp, repairing everything on behalf of everybody else.

Aliza Pressman (00:19:23):

Let them is the same thing as all feelings are welcome, all behaviors are not. How so? Because you're letting people feel and be who they are, but your boundary is set.

Mel Robbins (00:19:37):

The let me part.

Aliza Pressman (00:19:37):

Yeah.

Mel Robbins (00:19:38):

That's when you say, let me tell you that your behavior's not welcome.

Aliza Pressman (00:19:40):

Exactly. And I think we have overcorrected because we had so little sensitivity of care and so little patience for how people feel. But we for sure have overcorrected to the point where if you're a sensitive loving person, you're like, okay, I guess they were feeling really angry. So I'm not going to say anything about the fact that they just completely destroyed whatever was in their path because of those feelings. And so I want us to come back from that overcorrection. That's incredible. So what's the worst parenting advice, Dr. Pressman? Of course we want our kids to be happy, but I guess the worst thing is when you're, nothing matters except that your kids are happy. And so you invest in that moment happiness in that moment, really understanding what they want, not what they need, but what they want to be happy. And so there is no sense of safety and boundaries and those rules do not exist. And it actually causes a lot of anxiety.

Mel Robbins (00:20:48):

How does wanting the best for your kids cause anxiety? Why is that bad parenting advice?

Aliza Pressman (00:20:53):

I should say this. Of course, you're going to want everything to go right for your kids, but in your actions, if you're clearing the path completely, and it's like you're trying to control the weather and how does somebody learn how to put on a raincoat and to put on their boots and to put on their coat because they looked outside and they were like, oh, it's snowing, it's raining. I know how to handle this. If instead it's like somebody was like, no, no, no, I don't want you to experience any of that. And so it's this investment in long-term life happiness. And also the happy thing is weird because nobody's happy all the time. And so if you're constantly trying to make sure how many of us have experienced somebody saying like, oh, no, no, I want you to be happy. What can I do to make you happy right now when you're not going to be happy right now you're going through something. When

Mel Robbins (00:21:50):

Somebody does that with me and I'm going through, I'm like, stop asking me.

Aliza Pressman (00:21:53):

Literally, that is so annoying. So if we're chasing the happy instead of doing our thing, relationship, reflection, regulation rules, repair or even shorter, all feelings are welcome. All behaviors are not. We're trying to create a greenhouse for these beautiful flowers to bloom, but then they cannot exist otherwise.

Mel Robbins (00:22:18):

So if the perspective of I just want my kids to be happy or I just want the best for my kids, is the wrong focus, what would you rather we say,

Aliza Pressman (00:22:28):

Rather we say, I want to raise the child I have in the environment that helps them thrive by building skills, just by building skills and by doing the things on my end, cleaning my side, because we can't control our kids, but we can be this sort of presence that more often than not is available, loves them for exactly who they are and sets appropriate limits and boundaries and makes repairs when necessary. But we're giving them tools, not just by actually giving them tools. And we can certainly talk about that, but by having those tools, that's the best gift.

Mel Robbins (00:23:09):

So it starts with you.

Aliza Pressman (00:23:10):

It always starts with us.

Mel Robbins (00:23:12):

How much do early experiences truly shape you? I mean, if you blew it during the early years or your parents were horrendous, are you screwed up for life? How bad is the impact of an early childhood or good.

Aliza Pressman (00:23:29):

Early childhood is no joke. It's really important. But just when I say what I'm going to say, I want to remind everyone that relationships are so dynamic and we grow and we change, and there's always hope. So I don't want anybody to be like, I give up. I've done wrong. This is over. I know that nobody listening has that mindset or they would not be listening to your podcast, but I just, so early childhood is crucial. It's kind of how we get this real wiring of we love and how we experience being loved. Is the early attachment relationship very important between the primary caregiver and the child? It really is. Are the early experiences very important? Is the environment very important? And also it's never too late. It's just never too late.

Mel Robbins (00:24:30):

And it also sounds like a big factor is also the temperament of the child that there are. And I think if you've got siblings or you have multiple kids, you recognize, you see it that every parent is a different parent to every child and none of your brothers and sisters had the same childhood as you did. They don't have the same temperament. And every time a parent becomes another parent to a child, you actually are a different parent.

Aliza Pressman (00:25:06):

Totally. So you've got yourself as a different evolving parent for better or for worse, usually better. But it also depends on the circumstances. I got divorced when my oldest was not even five, and my youngest was just about to turn three. And I was hearing the research in my head over and over about these early years, and I was just so devastated. I was thinking, oh, I'm going to be in distress and that's going to impact my kids. And so what do I need to do? How do I need to do this? I need to do this with that knowledge. Not to scare myself, but to just be super intentional during this time because all things being equal, I would not have done it at that time because it is a very sensitive period.

(00:25:55):

But we can do workarounds and temperament really matters. And so that's the other thing. That's why some kids really can thrive under almost any circumstance. They're like dandelions. They can grow through the cracks of a sidewalk and you're just like a whack-a-mole and you can't believe it. And other kids are, it's a continuum. Of course, nobody's in categories, but just for ease of talking about it, I think it's helpful to think like an orchid child is going to bloom under the best of circumstances and be incredibly robust, but in the worst of circumstances, if you've ever tried to raise an orchid, I have, it's It's not pretty. No, it's not pretty. So you have to also take that into account.

Mel Robbins (00:26:37):

So can you explain that metaphor for temperament? Because in the five principles of parenting, you talk about orchid children versus dandelion, dandelion children. What does that mean?

Aliza Pressman (00:26:50):

Thomas Boyce did this research and it's really beautiful. I think as long as you take it all with a grain of salt because people are not just in categories of flowers, but if you have more than one kid or more than one sibling, this is true. Which is there are orchids, tulips and dandelions and the dandelions, and I'm going to say something that can sound daunting, but I think it's also inspiring. Parenting is the most powerful environmental input for our children.

Mel Robbins (00:27:25):

Parenting is the most powerful environmental input for children. You can be in the worst of circumstances,

Aliza Pressman (00:27:31):

Worst of circumstances,

Mel Robbins (00:27:32):

And have a steady, loving, safe parent.

Aliza Pressman (00:27:34):

It is incredibly protective. It's incredibly protective. And we can talk about that. I think that research is exquisite separately. When you think about how anyone responds to their environment, an orchid responds quite sensitively to their environment. They're going to be attuned to everything going on, and they need a very specific set of sunlight, water and soil in order to thrive. But then they're magnificent.

Mel Robbins (00:28:02):

Yes,

Aliza Pressman (00:28:03):

A tulip is sort of somewhere in between what might've been considered slow to warm up, and yet they can do pretty well. And then dandelions, you really don't need to do much, but love them more often than not, and set some boundaries here and there and they're going to be fine. And I think it can be really flattering if you have a dandelion like I am agam this, and then you get an orchid and you're like, oh, wait a second. This is a little more challenging. I have to put a little more thought into this environment.

Mel Robbins (00:28:37):

You said that the parenting is the single most powerful environmental factor for a child. And we talked about the fact that a child could be in a very unsafe, stressful, physical environment or country or house. But if you have a safe protective parent that feels like home, that is a very stabilizing force. And I want to be sure just to validate if it's true that you could also be in the most safe, affluent, amazing household in terms of the physical space. But if you have unsafe parents or people that are not there consistently, that still is the single biggest environmental environmental factor who the parents are.

Aliza Pressman (00:29:32):

And I say this with so much compassion because when I first learned about this literature, I was like, that is daunting.

Mel Robbins (00:29:40):

Well actually think it's very inspiring because I do too. We're also busy chasing all this stuff for our kids. And the research is pointing to the fact that it's actually what you personally provide with your energy. And whether or not, more often than not, you're showing up in a way that makes the child feel loved and seen and accepted. And I think for anybody that grew up in a household where you look around, you're like, well, it's not like I was beaten.

(00:30:13):

But there's something that feels really off the research is probably pointing to is you had all the stuff on the outside, but in terms of the parents being able to provide the most important and powerful environment, which is their own emotional stability and presence, you didn't get that.

Aliza Pressman (00:30:37):

So it sometimes gets replaced like somebody found an amazing coach or mentor. So one adult in your life that has kind of got your back, that loves you for who you are, not the splendor of your accomplishments, all that stuff buffers the impact of even the most horrific stressors. So when you think about that's what the research says, that's what the research says. So there's toxic stress. We talk about stress all the time, but we need to distinguish between what kind of stressors because some stress is great. That's called positive stress and that leads to growth. Any stress that is not long-term harmful, it's just like short-term, those little weights that you're lifting, they're uncomfortable, but that it leads to growth. We need that stress in order to be resilient. Humans, it's not possible to grow resilience without having positive stressors. Then there's tolerable stressors, which are the things that you wouldn't wish on people, but they happen. Divorce, death of a loved one, things that are really hard, but in the presence of a loving, supportive caregiver can actually grow resilience. And then there's toxic stress. You would not wish toxic stress on any human ever. It's horrible stuff. But what I think is spectacular about this research is that if you take what would be listed as a toxic stressor, like what? Witnessing abuse and you have one, just one caregiver that has that safe, stable, connected relationship, it moves the categorization of the stressor from toxic to tolerable. And to me, the fact that the parenting environment can buffer the impact of those kinds of things is so relieving, and we can do that.

Mel Robbins (00:32:31):

You also, Dr. Pressman say that parenting has nothing to do with the kids.

Aliza Pressman (00:32:38):

It's about us. I mean, there's no way around it. Part of the reason why I said relationship, reflection, regulation, rules and repair, none of those have anything to do with kids. How you're raising your kids. When you're thinking about those five principles, it asks nothing of them. They get to be themselves. They are growing. You are creating that relationship. You're cultivating that relationship. You're doing the reflecting. You're not asking them to reflect. You are doing the regulating, you are making the rules, and you are initiating the repair. So it's actually much easier because you can't control other people. I mean, we try constantly. It is so obvious when you put it that way. I know. It's just like a lot of times people come to me, we're in conversation, I'm like, how can I help? And they're like, I need my child to be more out of control. I, it's just like, well, okay, we're going to work on the thing you can control, which is how's your regulation going? And then once people realize that, it's like, oh, things changed in my house. My child did develop better self-regulation skills over time once I did my work.

Mel Robbins (00:33:51):

And that brings us to a huge topic in the book, which is about raising emotionally healthy, resilient kids. What's the biggest myth? Parents believe about raising healthy, resilient kids?

Aliza Pressman (00:34:05):

The biggest myth is that you can't be sensitive as a caregiver if you want to raise resilient kids that you shouldn't coddle that. It's coddling to be too sensitive and attuned. And so what happens is you get extremes in resilience. In attempts to build resilience. You either get the, I'm not going to acknowledge this. This is hard and this kid has to experience hard things or you absolutely get an overcorrection of, I don't want them to experience any hard things. And neither of those are good for resilience building the thing that is important is you can be as sensitive as you feel comfortable being to honor whatever your child is experiencing in their feelings. But it goes back to all feelings are welcome knowing that you can have a sensitive parent who's like, I see you. I see what's going on for you. I'm not changing what the plan is. If I'm sending you to a job that you're really scared to do, I don't know what job that would be as a child.

Mel Robbins (00:35:15):

Or we're changing schools.

Aliza Pressman (00:35:17):

Yes, okay, there we're changing schools,

Mel Robbins (00:35:18):

Or you're upset that mom and dad are getting a divorce or you're

Aliza Pressman (00:35:21):

Or you're upset mom and dad are going to dinner for that matter. Yes, I hear that all the time. Parents are like, I can't leave the house at night. I can't do the weekly date with my partner because it would be too upsetting for my child. Or I can't have them sleep in their own room, right? Just so I think maybe what it is is the extremes of the rigidity of saying, I'm going to force you to do this uncomfortable thing and I'm not going to give you the connection that you need to get through it or the other side of it of I won't force you to do anything. And I think that those two extremes, they both create potentially very, very absent of resilient, fragile, fragile kids. And it's like we have to decide. I err on the side of sensitive, so I have to work really hard at keeping those boundaries and saying, I know you're struggling. I know you don't want to do this. I know you're safe. I'm here for it. If you want to cry about it, but then you're still going because I hate you, Mom, totally. Because I would hear that. I'd see the welled up eyes

(00:36:36):

And my inclination would be to say, I don't want you to feel that feeling and I want you to know that you're safe with me, so I don't want you to experience that, so I'm not going to make you do it. And then that grows fragility.

Mel Robbins (00:36:49):

I completely screwed this up by the way. This was one of the big mistakes I made as a parent

Aliza Pressman (00:36:53):

Because if your child was uncomfortable, you were like,

Mel Robbins (00:36:56):

Don't have to do that. You can sleep on the floor for six months, which only made the anxiety and the fear way bigger.

Aliza Pressman (00:37:02):

Bigger,

Mel Robbins (00:37:03):

Yes,

Aliza Pressman (00:37:03):

It's really hard. But then on the other side of it, the thing to be careful about is if your person who's like, I don't feel that sensitivity and connection, I am so good at those boundaries, I don't want you to think about those boundaries anymore. Because if you want to build a resilient kid, you probably need to be a little bit more attuned. You've got the boundaries down.

Mel Robbins (00:37:22):

What happens if you're too tough? What happens if you have an orchid who's very, very sensitive and it's frustrating as hell and you do not validate what they're feeling? You've just had it with them.

Aliza Pressman (00:37:35):

I mean, again, so sometimes that happens. Who cares if that happens? More often than not, what your message is is you are defective. You kid or defective. You shouldn't be feeling those feelings. And so they will either hide them, they're not going to stop feeling them. Nobody stops feeling them. They just don't share that with you. And so you lose the thing that is most protective for resilience, which is relationship. And so that's why that tough love and the absence of the connection can be harmful.

Mel Robbins (00:38:07):

I find a lot of times when I talk to somebody like you who has all of the research and the amazing simple things that we need to do, and you then start to assess the way that you were either raised or the way that you raised your kids and you recognize, I wasn't raised the way you're talking about, but I'd like to be better. Where do you start when you have this realization that you would like to raise your kids differently? You would like to be a different parent?

Aliza Pressman (00:38:46):

I think it always starts, almost always, it starts with a breath, with your hand on your heart and just releasing some of the pressure because you did not make the choice of how you were raised. And you can love your parents deeply and know that they were doing the best that they could do with what they had, with the resources that they had and that you can still do a little bit better because you listened to this podcast episode and you were like, I think I have more resources now. And of course, there's many bigger resources that people need, and that moment of self-compassion gives you the compassion that your parents can get so that you can kind of release that and move forward. And then I think every time you pause before acting with your kids, you're doing it. You're just giving a little bit of space. That's beautiful.

Mel Robbins (00:39:49):

What if you realize, my God, I've made a lot of mistakes. I was the parent that was indifferent or cold or distracted or I had a lot of anger, or I really screwed up the divorce because I didn't want the divorce. I complained about their other parent nonstop. I was angry. I was suffering. What do you do when you have this realization? Boy, I really wish I could go back and get a do over.

Aliza Pressman (00:40:20):

I would imagine that we all would be so happy to receive from whomever this adult was in our life, that call or that coffee or that walk where they say, I don't like how that went. I don't like how that went. I can't take it back, but I want to move forward in a way, if you'll have me. That's different. Now, I don't know anybody who wouldn't want that unless they experienced abuse and neglect, and that's a different conversation because,

Mel Robbins (00:40:58):

But even that acknowledgement in those situations or whether you want a relationship with them, even the acknowledgement that I am at fault, I was wrong. I see that and I need to say it so you know that I've acknowledged that.

Aliza Pressman (00:41:17):

Absolutely. And then the person on the receiving end can decide whether to receive it.

Mel Robbins (00:41:21):

Yes,

Aliza Pressman (00:41:22):

But you've done your part and you also have to accept that they might. You have to let them decide that that's not for them anymore. In so many circumstances, just being open to that new relationship is all you need to do. And then it's work. Then you just kind of recalibrate together. I do want everyone to know that the onus is on the parent. It's never on the child.

Mel Robbins (00:41:50):

Say that even when you're an adult.

Aliza Pressman (00:41:51):

Even when you're an adult,

Mel Robbins (00:41:53):

Why is the onus on the parent?

Aliza Pressman (00:41:55):

Because it wasn't the child's decision. It was never on the child. We are fully responsible for raising our kids. They are not responsible for how we feel, how we act, how many times we might accidentally let slip out of our mouths. I wouldn't do that if you didn't X, Y, and Z, but it's never, the onus is never on the child, and you are always, even as an adult child, you are always the child. That doesn't mean that you're not going to care for your elderly parents and love them. And maybe this is too much for them and you're like, wait, they didn't have that upbringing either. They might not know how to do this, but if they're coming to you, then they've started to know how to do it.

Mel Robbins (00:42:47):

I don't know why. I feel like I've never heard, even when you're the adult, you're still the child and it's still on your parents.

Aliza Pressman (00:42:56):

I mean, I know that people would love for it not to be because it can feel, particularly when you think about different generations and just culturally, but what I'm saying has nothing to do with caring for your elderly parents, loving them, making sure that they feel okay in a world that is totally changed, but you are not responsible for repairing a relationship That was their responsibility that is on them. It's just never on the child, no matter how old you are.

Mel Robbins (00:43:33):

Wow. I think that's a hard pill for a lot of parents to swallow. I know, especially with adult children,

Aliza Pressman (00:43:39):

I understand you are responsible for deciding whether you're going to have forgiveness and compassion for your parents. That's on you. But the repair, repair has to be on them. If they can't do it, if they can't initiate it, then it's not your responsibility. Now, that doesn't again mean you need to be imprisoned by that because they could be long gone and you can forgive them, and that is so powerful. But the repair, the reconnection has to come from them. It's never a responsibility

Mel Robbins (00:44:13):

Otherwise It's going to always be the same dynamic

Aliza Pressman (00:44:16):

You're still in the cycle

Mel Robbins (00:44:16):

In this power struggle.

Aliza Pressman (00:44:18):

Yeah, it's heartbreaking. And then you're also, you're trying to do something that's not doable, and so you're going to eventually, again, question your own worthiness.

Mel Robbins (00:44:31):

It brings me to this quote that I love that you have in your book, the Five Principles of Parenting. It's on page 60, Carl Jung, quote, the greatest burden a child must bear is the unlived life of its parents. Can you unpack them? Pack that because you're right over sacrificing our dreams for our children doesn't ultimately do them any favors. What does this mean?

Aliza Pressman (00:45:00):

There is a martyrdom in motherhood in particular.

Mel Robbins (00:45:05):

Can we go there, please?

Aliza Pressman (00:45:06):

Yes. And it's motherhood.

Mel Robbins (00:45:09):

Explain Marty him because it's a big word.

Aliza Pressman (00:45:13):

The idea there is some weight we give, this weight we give to a mother who is sacrificing herself for her children. That is the ultimate mothering that mother. You hear this time and again in speeches about mothers, she gave up everything for me. She gave up her dreams For me, it's deified. You are so you miserable. Basically it's saying you don't have your own thing.

(00:45:50):

You are miserable, and your whole center of your life is this act of mothering. Now, I'm a mother. You're a mother. We know that our kids are in so many ways, the center of our lives, the sun, moon, and stars. But who among us wants to be that burdened by being the center, by leaving, going off to life and college and whatever, and thinking, my martyr mother has nothing. Her purpose is nothing except for me. That doesn't feel good. So that's one problem. But also it sets a really unhealthy message for women about what mothering even is.

Mel Robbins (00:46:36):

I also think it can create a dynamic where there's a underlying resentment and loyalty owed because of the sacrifice. I gave up everything for you, therefore you owe me X, Y, and Z. And if you don't give me that, there is this resentment because it feels like you don't appreciate all that was given. Feel, punished, feel like this is something that does not get talked about a lot. That it is an example where you're right, you do hear it all the time in speeches. And that's not to say that moms aren't amazing and that the sacrifices that you give up, you give a lot of sacrifices to be a mom. We all do.

Aliza Pressman (00:47:26):

We all do. Which is why I think it's hard to have this conversation because it's not, it's grayer,

Mel Robbins (00:47:31):

But I chose to be a mom, so I'm choosing to give the sacrifice not an expectation of something.

Aliza Pressman (00:47:38):

It's not an expectation. I think you actually right then and there made the distinction that is so important because if I'm making this choice, I'm doing it with absolutely no expectation. I'm doing it in that case, not as a martyr, but as a mother.

Mel Robbins (00:47:54):

Let's say the person listening is like, okay, I really blew this, or I'm failing or I'm going to fail. What would you tell somebody who feels like they're failing at parenting right now?

Aliza Pressman (00:48:08):

I don't believe you, first of all. And I believe every feeling that everyone's having, but I don't believe that you are actually failing because you're here. There is no way. It is a self-selecting group of people that are curious, that are listening to this. And you cannot be a curious parent without being a good enough parent. So that's my first thing is denying your feelings. And then I would say, make a choice. Do you want to move forward in this new way? Do you feel like this is surmountable? I think it is.

Mel Robbins (00:48:44):

And there are so many parents right now in survival mode.

(00:48:47):

In fact, there's recent research about how the stress associated with parenting is its own form of chronic and acute stress. And so if you're in survival mode, which I feel like I was in for almost like a 10 year period with my kids when they were really little, desperately trying to make the ends meet, trying to keep the job, trying to get groceries and dinner, trying to get people just doing the best you can collapsing into bed, drinking too much because I am trying to turn my brain off. If that's you, where you're just surviving and you're stressed, how do you start becoming a parent that's more intentional? What's the first step after patting yourself on the back for being here? Which I am glad you're saying that because I do think being interested in learning and doing better is something that is worthy of acknowledging and celebrating, but what's the next thing I do?

Aliza Pressman (00:49:53):

And so knowing that you can acknowledge like, okay, I'm not alone here. This is a pretty global feeling. So if I'm not alone here, how can I figure out community for me? Because this hokey put your oxygen mask on first is real. So what are the things that I need to do in my day that maybe I'm putting into my kids? I think it's better for them that I can take out of the day.

Mel Robbins (00:50:24):

Can you give me an example?

Aliza Pressman (00:50:25):

Sports.

Mel Robbins (00:50:26):

Sports, what do you mean? They don't have to be on 15 sports.

Aliza Pressman (00:50:28):

They don't have to be on 15 teams where you have to drive 500 hours a week to make sure that they're getting all the things because sports is so important for development and teamwork and maybe getting into a college or something because you're doing it at the expense of functioning. And so you aren't even able to be the parent that has the good enough relationship. You're too busy with all the busy stuff. So I would take off the table the things that you are pretending are better for your kids. And I would say let's get back to the basics. How often am I losing my mind? What do I have to take off the table when it comes to losing it with the kids?

Mel Robbins (00:51:09):

Let's talk about meltdowns.

Aliza Pressman (00:51:11):

Okay.

Mel Robbins (00:51:11):

If you've got a kid who's constantly melting down, what do you do?

Aliza Pressman (00:51:20):

First, if you have a kid who's constantly melting down, I would want to do a lot of reflection, like spend one full week not changing a thing, but noticing what starts that meltdown,

(00:51:34):

And then what do I do in response? So you want to look at what happened before the meltdown. Then you want to look at the meltdown and how you respond to it. And you will get so much information that week because what you might find out is this kid melts down when I am, my insides are spinning out. I'm rushed. I've got a thousand things to do. It's coming across. And that is when they choose to melt down. So that means, okay, back to us. I need to slow down. I need to take a breath because I am really, I don't want us to meet them where they are. We want them to meet us where we are.

Mel Robbins (00:52:16):

So in addition to doing a one week of observation, because I would imagine you could probably do this with the adults in your life, and you could see that there are patterns to people's meltdowns, there are patterns to when your partner erupts over things. And that if you also apply that temperament model of, oh, am I dating an orchid or do I have a dandelion or a tulip? And kind of understanding that temperament piece. And if I'm really getting the power of what you're saying, it's not about them. It's about you reflecting and you understanding that changing your approach to match who you're dealing with and what you're dealing with is where the power is, particularly with parenting, but kind of with everybody,

Aliza Pressman (00:53:07):

Kind of with everybody, it's like there's a saying, I have no idea who said it, but when a flower doesn't bloom, you change the environment, not the flower. And so we really want to change the flower sometimes. And if we change the environment, and in this case the environment is like, okay, the transitions need to be less haired. I need to figure out a different way of scheduling because we're hitting the same challenge every week. And then separately, we can let tantrums happen and we don't have to fix them in real time.

Mel Robbins (00:53:37):

What is a tantrum? So Dr. Pressman, when you hear a kids being difficult or they're throwing tantrums, what is the person feeling?

Aliza Pressman (00:53:47):

To me, a tantrum is an indication that that person does not feel safe. They feel threatened. So they go into fight because there's fight, flight or freeze, and you go into fight mode. What you're saying is, my alarm went off, my internal alarm went off, that I am under threat and I don't know how to deal with it except to fight. And so you're seeing red, and it's the same thing as if somebody was coming at you with a knife. You just feel under threat. And when you're little, that threat can be because you've got a blue cup and not a red cup. It doesn't understand the threat as real or imagined. It feels very real. And so what we have to do is help our kids learn to distinguish and ourselves the difference between real and imagined threat so that you have access to say, I'm starting to feel these feelings. Like when I'm about to throw a tantrum, I can tell you right now my hands clench.

(00:54:51):

That's a clue that I'm about to lose my mind. So for me, if my hands are clenched and we all can figure out what those little signs are, that's the sort of slow warning beep of like, I better figure out how to not go into, there is a threat of an attack. So I know for me, there are three things that get me out of it. The first is breathing. Because you can't breathe and run away from a saber tooth tiger. Our primitive state would stop all that. You wouldn't take a sip of water. You can't be angry and take a sip of water, try it. It's not possible because the message when you take a sip of water is you're safe to take a break and take a sip of water or putting your hands under cold water. Those three things, those three things, take a breath, take a breath, take a sip of water, put your hands under water. And basically you're saying we have to get the fire extinguisher before it goes too crazy and causes too much of a mess. So I really want people to work on that for themselves. And your kids get that tool by watching you not meet them at their tantrum.

Mel Robbins (00:55:57):

Well, if you don't have kids, do this with your parents. Do this at work.

Aliza Pressman (00:56:01):

There's anybody. There is so many people that are going to be in your life

Mel Robbins (00:56:06):

That are going to make you angry or make you want to erupt and learning how to, for me, it's like a volcano. I feel like heat rising and then my tone of voice shifts immediately. Just like when somebody hangs up the phone when I was little and the tone of voice had shifted immediately. I'm just repeating this mood thing and it can happen like that. And so I love that advice. Take a deep breath. Take a sip of water, put your hands under cold water, and you're signaling, all right, let's just stay calm.

Aliza Pressman (00:56:37):

Because we're safe. And then your child who's in the middle of a tantrum or that person who's maybe even picking a fight with you sees that you are not erupting as well. You are not panicked. You remind yourself that you are safe and your child is safe. They will go through the tantrum faster. It will be over and you move along.

Mel Robbins (00:56:57):

And just redirect.

Mel Robbins (00:57:00):

I would love to talk about advice for dealing with other adults because the person that is spending time is investing in themselves. But let's say you have a partner who is just phoning it in. You're the one reading the books, you're the one listening to the podcast, you're the one trying to calm yourself down, and they're still snapping or not receptive to trying different ways of approaching Dr. Pressman. What do you do in those situations where you're married to somebody or you're partnered with somebody that is not interested in doing better?

Aliza Pressman (00:57:49):

Share this episode, share resources that are not, I know better than you, but they're more like, I think this is interesting. Tell me what you think. Open up a dialogue. And also remember, you cannot control other people. You can't control their journey. You can't control their path. So the work is to keep doing what you are doing. They will witness that, and then you can, if they're curious about it, you have ways to say, here's where I came up with this, or This is what I'm thinking. They might see a more successful relationship. They might see that you're doing a little bit better, and they might learn by watching that. But if you just say, I've figured this out, you need to be better. It's just not going to go well.

Mel Robbins (00:58:44):

I think you could also appeal to what you're offering. Sounds more peaceful, honestly, because there's a lot of conflict in side households. There's a lot of bickering and arguing and not talking and frustration and resentment. And one of the things that I wanted to ask you about is you recently got remarried and you now are navigating a blended family. And I would love to just hear Dr. Pressman, your observations about based on kind of the research and some of your experience with patients or even in your own situation, what do you think people get wrong about trying to blend families or dating somebody that has kids and becoming the new person in their life? And what do you want people to know?

Aliza Pressman (00:59:43):

I want to be very careful. This is really hard stuff because as the adult, you're navigating dating again, that was supposed to be off the table, and you have your own kids potentially, or maybe you've never had kids, but you definitely have a different parenting style, even if you agree on everything. We're all different. We have different approaches. We came into this with different backgrounds. And so I think in terms of dating, people introduced partners way too early. You should wait because your kids don't need to experience the revolving door. They are not your best friend. They do not need to approve of everybody. You need to know how you feel about someone, enough that they're worthy of meeting your kids. Because when you see that over and over again, it really messes with people

Mel Robbins (01:00:39):

Based on the research after a divorce, how long should you wait before you introduce who you're dating to your kids?

Aliza Pressman (01:00:46):

I mean, the research suggests, particularly with the younger kids, that you wait a year.

Mel Robbins (01:00:50):

A year,

Aliza Pressman (01:00:50):

Which is a long time. And anytime anybody asks me, they don't like that answer.

Mel Robbins (01:00:55):

But imagine the discipline it takes and the protection that you're displaying of your children and the stability that you're actually creating for your kids.

Aliza Pressman (01:01:07):

Yeah, the exceptions are when it's just not feasible. But if you have a joint custody situation, then you very much can date somebody and get to know them. Now, if it's getting so serious that you're talking about being madly in love and getting married, then you can bump it up a little because you've already made that decision. But the reason why you want to take time is you need to learn how to be in a transition period with your kids so that they feel stable. And then you can start introducing other factors. But it's destabilizing. There's no question.

Mel Robbins (01:01:43):

Well, if you really stop and think about the research that you've shared, that you as a parent are the single most powerful environmental factor in your child's development, and what they need from you more than anything is safety. They need to know that you're there. They need to know that more often than not, they're going to be greeted with love and reason and care and your presence. And if you are going through a divorce or you are going through a period of grieving because one of the parents has died, that there a major transition going on. And if you then become so distracted with your new love life that you insert that too soon in a period of time, that your kids need you to be the single most powerful, stable environmental factor in their development through the transition, I would imagine it's very disruptive and damaging. What is the research?

Aliza Pressman (01:02:42):

So it definitely undermines the future relationship too. So if you're feeling like this is the person, give them the best shot at having a good relationship with your kids by not rushing it,

(01:02:54):

And if it is the right person, they're going to take the time with you. They're right there with you. Now, if circumstances are such that it needs to be sooner, that's okay, but be as We can't be sure of anything. And you certainly, I can hear what people might say, which is, well, how I know for sure if they haven't interacted with my kids, I've got to see how they are with my kids and I think that's step two. But we did make the choice to have kids and we do need to give a longer runway because they are in a phase of life where they are forming and we want to proceed with caution because this is a tender time and by tender I mean easily influenced. And so you just want to be thoughtful and if you don't have a year, certainly give it as many months as you can to really understand this adult relationship that you're in.

Mel Robbins (01:03:51):

I have a friend who basically was a single mom, dad bounced, went off, had his own life, had nothing to do with the kids, wasn't involved financially, nothing. And now the kids are adults and dad is back in the picture and dad has a lot of money and it is extremely painful to see this happening. Even though your kids have a right to have a relationship separate from you with their other parent, how do you manage those sort of feelings when you're dealing with an ex, whether they're present or they're coming back and you just feel like it's just not fair.

Aliza Pressman (01:04:39):

It's unjust.

Mel Robbins (01:04:40):

Yeah, it's unjust. Or the kids go to the other parent's house and everything's the opposite of what you're trying to do. What are some of the phrases you can say, you know what I mean? That would just burn me alive. I'll just come right out and say that would be a very, very challenging situation.

Aliza Pressman (01:05:03):

No, I mean my shoulders are going up, hearing the story. Sorry, I'm like reminder that it just takes one.

Mel Robbins (01:05:12):

What do you mean? One,

Aliza Pressman (01:05:13):

It takes one parent or a loving caregiver with whom you feel that safe, connected self, the stability and all of that. It just takes one for positive outcomes for kids.

Mel Robbins (01:05:23):

And Dr. Pressman, is it okay if I allow myself to be arrogant and feel better than that? I'm choosing to be the one just taking the high road. That's okay. I don't have to do this. I don't have to be,

Aliza Pressman (01:05:37):

You don't have to pretend

Mel Robbins (01:05:38):

Gracious and all that about it. I can just be like, okay, I'll be the better one.

Aliza Pressman (01:05:41):

I'm taking that on.

Mel Robbins (01:05:42):

Okay. Alright. I just want to make sure

Aliza Pressman (01:05:44):

No own that, have that. I wouldn't say it to the other parent.

Mel Robbins (01:05:47):

Well, of course not. I wouldn't say to my kids either, but I'm just definitely trying to leverage something in a situation where just doesn't seem fair.

Aliza Pressman (01:05:55):

It is unjust except you are the one and when you are the one, there is nothing more powerful life in the environment of your child. And so that even though it is painful and even though it is unjust, it is incredibly powerful to keep reminding yourself, I'm not one, this is my job and I'm doing it more often than not and sometimes it feels really crappy and unjust, but I'm doing this for me because I will feel better. Because the shame that you feel when you can't do that

(01:06:31):

Isn't worth it. It doesn't serve you, it doesn't serve your kids and it is a near impossible task to have a really hard relationship with the co-parent and try not to badmouth them and try not to prove that you are better. But it does so much harm to the kids that it's worth reminding yourself, who is my real? Who do I really care about here? It's not this person who I have a terrible relationship with and for whom I'm driven. This is not the person. So if my real focus is on raising these kids, I'm going to do the thing that supports them, which is write in a journal, the terrible things I'm thinking, but do the things that are going to help serve my kids, which is to be that one person and you're going to screw it up. Sometimes we all screw it up. Sometimes I am divorced. I'm not always saying the most amazing things, but for the most part I'm not only saying nice things, I'm feeling them, I'm believing them. I'm trying to hunt for things that are good because everybody has something good. And if you can focus on that, it just goes into your body and that is reflected in the way you talk about the co-parent.

Mel Robbins (01:07:56):

I'd like also to remind you as you're watching or listening that your kids aren't idiots.

Aliza Pressman (01:08:01):

Yeah.

Mel Robbins (01:08:02):

You knew which one of your parents

Aliza Pressman (01:08:04):

Was the parent,

Mel Robbins (01:08:05):

The one that was safer.

Aliza Pressman (01:08:07):

Of course

Mel Robbins (01:08:08):

It didn't matter who bought you what or who had a nicer car or a bigger house or whatever. You knew. And your kids know.

Aliza Pressman (01:08:15):

They know that is such an important point. We don't ever need to tell them

Mel Robbins (01:08:20):

No.

Aliza Pressman (01:08:20):

We mostly don't need to tell them things they know. And that's why even when I said hunt for something good, it's because they know if you're faking it.

Mel Robbins (01:08:29):

I also feel like there must be a hardwired desire to always feel connected to your biological parent and so that I haven't been through it, but being angry at your kids for wanting that is just going against the nature.

Aliza Pressman (01:08:52):

Yes, it is actually harmful to them because their biological parent is a part of them. So if you're saying something about that person,

Mel Robbins (01:09:06):

Oh wow, I never thought about it that way.

Aliza Pressman (01:09:09):

If you do, it will help you not say those things like I'm shit talking part of who they are. You would never say something like that to your child about your child. So their biological connection is still a part of them.

Mel Robbins (01:09:27):

Is there research about what happens to kids when parents' trash talk? The other parent, what does the research say?

Aliza Pressman (01:09:34):

The research is that the higher conflict, the relationship between the co-parents and the more they bring the kin to it, the worse outcomes there are for both intellectual development, emotional development and general, all the positive outcomes, executive function skills, kind of everything. High conflict divorce is really not good for kids. It's the thing that is the hardest. I know it is so hard to ask that of people, but there is something so powerful about understanding how much that conflict harms kids so that you can do as much as you can. You can't do everything. But again, more often than not, if you can relieve them of being part of that conflict and even stop yourself from having the conflict and people are terrible to each other. Terrible. There are terrible stories, but we are wired for resilience and we are wired for love. And so those things will all come back. But they are so terribly challenged when kids are in the presence of high conflict relationships.

Mel Robbins (01:10:42):

And so with the number one rule to adopt be, don't speak ill

Aliza Pressman (01:10:45):

Yes.

Mel Robbins (01:10:46):

Of the other parent because when you do that, you're actually speaking ill of your child because that parent, as much as you may hate them,

Aliza Pressman (01:10:56):

They're part of them

Mel Robbins (01:10:57):

Is still part of that child.

Aliza Pressman (01:10:58):

Yeah,

Mel Robbins (01:10:59):

I've never heard anybody say that before. That is so profound and important

Aliza Pressman (01:11:07):

When you think about it makes me so sad just thinking of the times that I've screwed that up. But when you really think, we talk with kids all the time about, oh, you got this from this parent and this from this parent. So of course when you start to say this thing about this person you love is terrible, there's no question that the child is going to say, wait. But that's a feature I have and I know that's the biggest challenge and you will screw it up sometimes, but the more you're aware of it, I just think it makes it easier.

Mel Robbins (01:11:43):

I know that there are going to be so many people that listen to this, that share this with their adult kids or they share it to their parents or they share it with their siblings.

Mel Robbins (01:11:52):

If you're listening to this and you are feeling the weight of what you just shared either, wow, that's exactly what it felt like when mom or dad was complaining about this or Wow, I really screwed this up. Dr. Pressman, what would your recommendation be to the person who's either feeling the weight that this was my lived experience as a child and it's never been validated or acknowledged by anybody or you're recognizing that you did and you just were in such a state you didn't know how to do better. What would the first thing be that you would recommend that somebody do?

Aliza Pressman (01:12:32):

If you are the parent who just felt like you couldn't at the time, it was too hard? Talk to your kid, however old they are, and acknowledge that was about me. I was having a really hard time and the way that I talked about your parent wasn't your fault and it wasn't okay. And that was where I was then. And here's what I've come to now

Mel Robbins (01:12:57):

And I apologize

Aliza Pressman (01:12:58):

And I'm so sorry that wasn't your burden to carry and work on it. Just keep working on it. It's incredibly beautiful. So whatever I say or any expert in this field says that makes you feel like I screwed up, please, please remember that the repair part is never expiring. Just acknowledge and apologize. It's acknowledge, don't give like I did it because that kind of apology is so annoying. If that is remotely part of the repair, it's not repair. Also, remember that repair doesn't necessarily look like an apology. It can be just reconnection. It's like we're back. We're back to feeling safe and connected together.

Mel Robbins (01:13:50):

Is that possible if you don't apologize for the things that you did wrong?

Aliza Pressman (01:13:55):

I'm of two minds about this because with younger kids, you can't apologize every time where its weird. Sometimes you just have to see that you're giggling again and sitting closer in front of the TV and all is well. Same in your romantic relationships. It'd be so hard to constant because you're doing these micro discord moments constantly. I think when researchers looked at this the first time, it was 33% of the time is attuned and the rest of the time is rupture and repair. That's a lot of tiny little tears.

Mel Robbins (01:14:28):

It means 30% of the time you feel connected to your parents. The other 70% were hurting each other, upsetting each other and then coming back. And the coming back's important

Aliza Pressman (01:14:38):

And the coming back is so important.

Mel Robbins (01:14:40):

Actually, it brings me to a question that I wanted to ask you that goes all the way back to early childhood development. Why is the game of peekaboo so important?

Aliza Pressman (01:14:51):

I love this game so much and it really does have this beautiful way. First of all, we all do it. We don't even know why we do it, but you walk down the street and you see a little kid or you're at a restaurant and how many of us have gone under the chair and then popped back up just to get a little smile out of them? But what it teaches babies and toddlers is you go away, you come back, you go away, you come back and it exercises the muscle of believing that the people you love always come back. And it seems so small, but it actually comes from learning about object and person permanence, which is just the developmental psych way of saying that people and things exist even when they're not in front of you,

(01:15:36):

Which is so beautiful and a huge developmental milestone that happens around nine months. So if you take a six month old and they're playing with your glasses and you took your glasses off and you covered them with a napkin, they wouldn't look for the glasses. They'd be like, I guess if the glasses are gone moving right along. But you see a nine month old and they're going to lift up that napkin and look for those glasses and that seems like a nothing burger except it shows you. They finally understand that when things go away, they come back. They're still in existence before that. Those glasses don't exist once they're covered. So you're playing peekaboo and you are exercising the muscle of mommy's gone and she's back and she's gone and she's back and they giggle and they laugh and it's a fun game. But you're also now helping them when they go off to school or childcare or just you're leaving the house for the night.

Mel Robbins (01:16:37):

What I love about everything that you've shared is that Peekaboo taught us they go away and then they come back at nine months. But what your work is doing in these five principles are teaching us as we get older and we're adults, is that that same principle applies that people go away. People do things that they don't mean to do. People hurt you in ways that they didn't realize or didn't intend to, but there are ways in which we can use this relationship and reflection and repair and all of the things that you're talking about to actually come back. And that's a beautiful thing. It really is all about coming back. It is so hopeful to think that no matter what has happened or how much time has passed, there is still this invisible string between a parent and a child that is there whether you like it or not, and that with a different frame of mind and with the tools that you shared, that you can come back to yourself and potentially you might also be able to come back in relationship with people that you didn't think you could. And so I'm just grateful that you're here and I'm grateful that you were very clear about where the onus is. And you are also very gracious about the fact that people can only do what they're capable of doing with their life experience and with the experience that they had being parented by their parents.

(01:18:21):

And so much of this isn't personal and that there's a lot you can do no matter how much time has passed or what has happened if you choose to really improve things with just about anybody.

Aliza Pressman (01:18:37):

It's so true. And I hate the idea that there's so much noise out there that you just feel like every word out of your mouth is going to have such a terrible impact on your kids or your relationship or whatever it is. And we need to get back to the hopeful stuff that's doable and that is on us, but not to the point where we're like, I feel so awful about myself. I'm now not doing any of it and I'm shutting it out.

Mel Robbins (01:19:02):

Right? Today, you've provided a roadmap to really see not only the hope, of course there's always something you can do, but that it does begin with you, which means you have the power and you're the one in control, and that's a beautiful thing.

Aliza Pressman (01:19:16):

Now I just have to make sure that I remember that for myself, which I have to remind myself every day.

Mel Robbins (01:19:23):

We all do.

Aliza Pressman (01:19:24):

Yeah.

Mel Robbins (01:19:24):

That's why everybody thinks I'm talking to them on this podcast. I'm actually talking to myself.

Aliza Pressman (01:19:28):

Totally. I believe you because I feel the same way.

Mel Robbins (01:19:31):

Dr. Aliza Pressman, thank you. Thank you for everything that you shared with us today. There were so many life-changing things that you said. My mind is completely spinning. I've got like 15 people to send this to. I feel like I'm a better person because of your work. And so thank you,

Aliza Pressman (01:19:57):

Thank you. And likewise, you are changing lives. It is so cool to watch. It's so cool to watch, and I'm so grateful. Truly.

Mel Robbins (01:20:07):

Feelings mutual, my friend, feelings mutual. And I also want to just take a moment and thank you. Thank you for listening and watching all the way to the end. Thank you for investing the time and making the time to be here with us. I am so excited to see what changes when you apply everything that Dr. Pressman shared and taught with us today. I want to see you sharing this with people that you care about. I also feel so hopeful about the fact that it is never too late to recognize the things that you'd like to change and to make amends for the things that you didn't do the way you wish you had. I love that you can always do better, that you can always repair both with yourself and the people that you want to be closer to and in case no one else tells you, I wanted to be sure to tell you as your friend that I love you and I believe in you, and I believe in your ability to create a better life, and relationships are central to that.

(01:21:01):

So I hope you take these five principles. I hope you take all the truths that Dr. Pressman shared, and I hope you apply them because there's no doubt in my mind that your life will be better if you do. Alrighty, I'll see you in the next episode. I'll be waiting to welcome you in the moment you hit play. I'll see you there, and thank you for staying all the way to the end, watching all the way to the end. Thank you for sharing this with people that you care about. I'm so excited to see what you learned and how this changes your relationships for the better. Thank you also for hitting subscribe. You're the kind of person that loves supporting people that support you, and that's how you can support me and the team here at the Mel Robbins podcast. Alrighty, I know you want to know. Okay, what should I watch next? This is the perfect video for you to check out next, and I'll be waiting for you. I'm going to welcome you in the moment you hit play. I'll see you there.

Key takeaways

Good enough parenting is more powerful than chasing perfection because it teaches your kids they can make mistakes and still be worthy of love.

All feelings are welcome, but not all behaviors are. This boundary creates safety while still honoring emotional truth in yourself and others.

One stable, loving caregiver can turn a toxic stressor into a tolerable one, profoundly changing a child’s development and resilience.

When you trash-talk a co-parent, you are also speaking against a part of your child, which can damage their self-worth and emotional security.