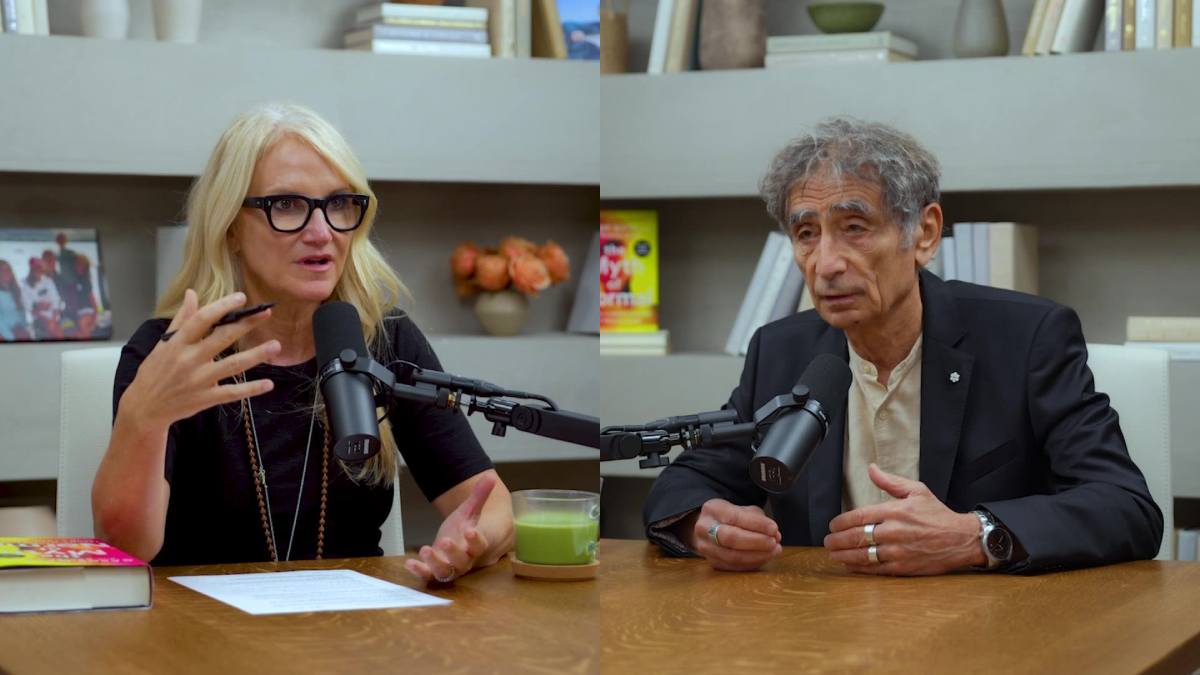

Episode: 364

This Conversation Will Change How You Think About Your Entire Life

with Ocean Vuong

This conversation will help you find meaning again.

If you’ve been feeling lost, stuck, stretched thin, or quietly wondering, “Does any of this even matter?”

Joining Mel is Ocean Vuong - one of the most acclaimed writers of our time and the bestselling author of On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous and The Emperor of Gladness, which is one of Mel’s all-time favorite books.

This episode is an invitation to pause, reset, and reconnect with yourself. It will help you stop judging where you are, release the pressure you’re carrying, and remember that you don’t need to become someone else to be worthy - or to build a meaningful life.

Even if you’ve never read Ocean’s work, this conversation will feel like someone finally handed you the words you’ve been searching for.

By the end of this episode, you’ll feel more hopeful, more centered, and more at peace with where you are - with permission to be exactly who you are, right now.

A meaningful life is not a life that you use to prove…that you are valuable.

Ocean Vuong

All Clips

Transcript

Mel Robbins (00:00:00):

If you feel lost in life, today's guest will help you find purpose and meaning. Ocean Vuong is a bestselling author and an award-winning poet. His debut novel earned him the American Book Award, the Mark Twain Award, and the New England Book Award. His newest novel, the Emperor of Gladness, debuted on the New York Times Bestseller list, and it's one of the best books I have ever read. Ocean is currently a tenured professor of creative writing at NYU, where he teaches in the MFA program for poetry and poetics.

Ocean Vuong (00:00:33):

A meaningful life is not a life you use to prove to yourself or others that you are valuable. A meaningful life is finding the power and the value where you are. Shame is so perennial for so much of American life, it's very much true for the poor. I remember, you know, like being in stop and shops local grocery store, and my mother, like counting how many tomatoes she can afford. All the struggles me and my family have gone through. They were all also sites of innovation and creative struggle.

Mel Robbins (00:01:16):

What would you say to somebody who's listening right now and is in that place where they are feeling a tremendous amount of shame and feeling very lost?

Ocean Vuong (00:01:27):

Dignity is about looking out what people have said to you that you should discard, and realizing that it's always part of you and being proud of that as, as, as a process of who you are. So owning all of your parts and not having to walk around with that shame. That to me is what dignity is. None of us chose to be here, but we stay, we stay around because we realize there's love here and it doesn't make poverty better. It doesn't make it even tolerable, but it gives your life a kind of significance when you realize that you are still capable of giving and receiving love. And that's no small thing. I hope people realize is that wherever you are, it's, it's enough. No one has to escape to be worthy.

Mel Robbins (00:02:21):

Ocean Vuong, welcome to the Mel Robbins podcast. Thank you so much for having me. I am so excited to meet you. I loved your book so much. I've given it to so many people, and I was absolutely honored when you said yes and said that you would come on and talk about purpose and feeling lost and about your work and the themes in your work. So thank you for being here.

Ocean Vuong (00:02:48):

Oh, thank you so much for, for recognizing what I'm trying to do. It's a, it's a deep, deep honor to be here and to share with this beautiful audience, um, all around the world. About what, at the heart of what I'm trying to do.

Mel Robbins (00:03:02):

Well, let's talk about that. Let's talk about what is at the heart of what you're trying to do. And if I really listen and take in everything that you will teach me today, how could my life change?

Ocean Vuong (00:03:17):

I hope people realize that if they don't already, that a meaningful life is not a life that you use to prove to yourself or others that you are valuable. A meaningful life is finding the power and the value where you are.

Mel Robbins (00:03:43):

What I love about that is that you're inviting us to consider that wherever it is that you are, even if you envision some possibility beyond where you may be, mm. That there is a way to feel dignity. There's a way to feel proud of who you are and what you're doing, that there's beauty in the life that you're living right now. Even though you may have a hope in your heart that things might change or move in a different direction, that learning how to reclaim that sense of self is really at the heart of your work

Ocean Vuong (00:04:21):

A hundred percent. And so much of language in our world and our culture has been captured to humiliate us.

Mel Robbins (00:04:29):

Hmm.

Ocean Vuong (00:04:29):

If we look at advertisements, political campaigns, if we look at, um, you know, emails, corporate messages, we're, we're bombarded by language that tears us down and says, we are not good enough. Um, we are, uh, constantly humiliated and debased in the way we experience language and the work of, I'm already getting emotional talking about this. Uh, the work of poetry and language arts is to reclaim the strangeness and the beauty of language so that the wonder and awe at the heart of it is recycled and reclaimed back to everyday use. Language is a strategy that has always been historically used to control people. And so when you realize that, oh, so much of this thing I use every day when it goes into the hands of corporations and politicians, it, you, it's manipulating me. Then you realize if I speak and use this material with, with deliberate attention and intention, um, then I can reclaim a portion of myself. And part of that is dignity. And a lot of my work is I'm interested in using language as a way to reconfirm self and communal dignity.

Mel Robbins (00:05:51):

What does the word dignity mean to you?

Ocean Vuong (00:05:54):

The ability to, to live without shame, um, and to be proud of parts of your life that people think, um, are are failures. 'cause in, in, in my short journey, I've learned that all the struggles that my, my, me and my family have gone through, they were all also sites of innovation and creative struggle. So to me, I think dignity is about looking at what people have said to you that you should discard, and realizing that it's always part of you and being proud of that as, as, as a process of who you are. So owning all of your parts and not having to walk around with that shame. That to me is what dignity is. And to me, it's like you are told that you gotta go up, go up the mountain, and there'll be a light that will heal everything. And what I realized was how, how long and inefficient realizing that is.

(00:07:04):

You know, it's like when my, I I was raised by illiterate women and because they were illiterate, they knew how powerful reading was. It was like sorcery to them, you know, because it's like, we don't know what it what it is, but we know how pop we know the world runs with language. So you have our blessing to go off and figure that out. I never had a mother that forced me to do this or that. She said, son, go off and learn what you can. And if you can't, there's always a seat next to me at the nail salon. So you go off and you go get your education. And for me, it took, it was a long circuitous path. It took me six years to get my undergraduate. I went to four institutions, community college, business school, dropped out, what have you. But you go off and then you tell yourself, and I think this is particularly true of the immigrant and the refugee, but I think it's true for, for all children of the working poor you, you tell yourself, I'm gonna go, I'm gonna go into that institution and I'm gonna figure it out, and I'm gonna come back and give this thing that was locked away inside the university libraries.

(00:08:19):

I'm gonna lo I'm gonna give it to my family, and then we're gonna find out why we're here and what happened to us. So it's kind of this mining and you realize that knowledge is so inefficient and it takes so long. Meanwhile, destruction is so efficient. You know, our, our our social services are gutted overnight by the stroke of a pen. Entire city blocks could be blown apart by weapons. It will take decades to heal and repair them. Destruction is so darn efficient. I human beings, one of our, our worst inventions was that we have found out, we have found the way in the 20th century to make instant ruins. You know, before that ruins took thousands of years to create, but now we can make ruins instantly, and we are still living in the aftermath of that. And I think that's also a metaphor for reparative learning, which is what so much of class being an a class outsider is. Right. You're, you're brought up with so much shame.

Mel Robbins (00:09:24):

What did growing up and feeling that shame that you feel when you're poor, when you're an outsider in a new country, what did that teach you about how to live in a world that is constantly mm-hmm. Sending messages that we don't support you or against you, there's something wrong with you. What did that teach you about life?

Ocean Vuong (00:09:53):

Shame is so perennial for so much of American life. It's, it's very much true for the poor. I remember, you know, like being in stop and shops local grocery store and my mother, like counting how many tomatoes she can afford. And I just think you're, as a kid, you're sitting, you're sitting there, you're standing in line and you're watching the cashier who's not that older than you look away because we're all in one ecosystem. They're not making that much money. So it's just like poor folks together. But what's unspoken is that, that deep shame. And none of us knew why or how to, to ameliorate it. And so you're sitting in line and you're watching your mom push two little plumb tomatoes back in the conveyor belt, and you're watching this kid who's probably four years old and you look out, look away because he knows, you know, outta respect again, that dignity, you know, like offering each other a little bit of dignity to look away. I'm sorry. Um,

Mel Robbins (00:11:21):

Why are you apologizing?

Ocean Vuong (00:11:24):

Because I wanna be clear and I, my voice is it wobbles. Um,

Mel Robbins (00:11:27):

You're very clear.

Ocean Vuong (00:11:28):

Okay, thank you.

Mel Robbins (00:11:30):

And I've, I've had the experience, but only I'm the mother

Ocean Vuong (00:11:34):

Mm-hmm.

Mel Robbins (00:11:35):

With the kids standing next to me. And I had the line rehearsed for when the credit card would not go through.

Ocean Vuong (00:11:43):

Yeah.

Mel Robbins (00:11:44):

And I would always cock my head and kind of look surprised and go, well that's weird 'cause it just worked at the gas station.

Ocean Vuong (00:11:50):

Yeah. Wow.

Mel Robbins (00:11:51):

And then I'd say, come on kids, let's go out to the car. I've got another card out there, which I didn't, and you don't forget that.

Ocean Vuong (00:11:59):

Yeah.

Mel Robbins (00:12:00):

But everybody knows and nobody knows how to talk about it, how to make it right. And looking away in that moment is a form of respect. 'cause you don't want the person who's dealing with that heaviness to feel the weight of your judgment either.

Ocean Vuong (00:12:18):

Yeah.

Mel Robbins (00:12:19):

And so please don't, don't apologize. Thank you for speaking and telling us the truth of your experience because, you know, for the person who doesn't know you, you're, in my opinion, one of the most decorated and awarded writers alive right now. The American Book Award, the Mark Twain Award, the TS Elliot Prize, the New England Book Award, the MacArthur Genius Grant, you are a professor at NYU. And so while your story began growing up in Hartford, Connecticut, immigrating here from Vietnam, your mom and the women around you being illiterate and working in a nail salon, you went on to take back language and write about dignity in the human experience.

Ocean Vuong (00:13:20):

Gosh. Mel that's that. Thank you so much for that counter and, and that opening. Um, I'm so grateful for that moment of grace, because I think one of the things about moving through class systems is that you always assume what you're going to say is going to be not legible. And I feel like, you know, both you and I know, and maybe a lot of your audiences knows too, where you walk into a room and say, well, do I really say it like it is? Or, and, and, and if I do, are they gonna look at me like I'm crazy? Um, or am I just outside the frame of understanding? And so you try to assume that what you're saying, um, is a breach. So you have to apologize for that breach. Right? Oh, I'm sorry, I'm gonna go here. Um, but I feel like we need to go here. Right. And you gave me such a beautiful moment of gr grace that I don't, um, really experience in the, in the, in the spaces that I now traffic in. But I think, um, there's two types of shame. There's the shame of who you are, which is ontological. You know, people like,

Mel Robbins (00:14:30):

What does that word mean? Not, that's a big word.

Ocean Vuong (00:14:32):

Yeah.

Mel Robbins (00:14:33):

Ocean. I like,

Ocean Vuong (00:14:34):

Um, the shame of yourself, right? Mm-hmm. So people, you know, like for queerness, many people shame us for our, for our ourself, our, our ontological presence, our being, which we cannot change. And then there's the shame of action of conduct, which I think can be really fruitful. You know, there, there, it would be great if a lot of our politicians felt a little bit of shame, right? Because that means there's recognizing that you can act on it. You can do something, you can repair something. And so I think in, in many cases, and so much of my childhood was, was about both of those shames. Yeah. The shame of being poor, which you had no control over. Um, then the shame of being queer, which you have no control over, and then the shame that what you're doing is not enough. So the shame of action, it's like, oh, I work so hard, but I'm not feeding my family.

Mel Robbins (00:15:27):

Hmm.

Ocean Vuong (00:15:27):

I work so hard, but I'm still stuck in this tenement. And, you know, my mother told me, I remember she got, she, she got, we were just talking one day before bed, and I just like to just talk to her before bed. I was like 10 or 11. And she turned to me and she said, I'm so sorry that our family is so stupid, we couldn't make it. It's been 10 years in this country. And other folks have started businesses that are lucrative. They've gone off to Houston and la other Vietnamese communities. They bought homes. And we can't figure it out. I'm sorry that we're just so dumb. That gets the heart of what it means to be poor, is that it's, you start to feel that you're not a good person.

Mel Robbins (00:16:17):

Hmm.

Ocean Vuong (00:16:18):

Because other people could afford to give. Right. The heroes in our public discourse are the, the one, the entrepreneur, the ones that can donate and give and rescue children and rescue the people. But when you don't, when you every day you don't have enough to even be the hero of your family, that you start to feel like you're the villain of your community.

Ocean Vuong (00:16:45):

And so, when I was a kid in that moment by my mother's bed, and in that moment by the grocery store seeing to the day I die, I'll see those plumb tomatoes roll back, uh, this dirty conveyor belt. You realize, I told myself, I'm, I'm going to use the shame and it's gonna propel me to understand it. So shame became my propulsive force. You know, I was like, I'm gonna use this to, to as wind to find out, because this can't be, there has to be a root to all this.

Mel Robbins (00:17:25):

What would you say to somebody who's listening right now and is in that place where they are feeling a tremendous amount of shame and feeling very lost, whether it is because of very similar life experiences that you've had, or maybe it's somebody who's feeling a lot of shame because their marriage blew up.

Ocean Vuong (00:17:49):

Mm-hmm.

Mel Robbins (00:17:50):

Or they got a health diagnosis and they're having a lot of trouble really just getting through the day, or they've really made some terrible decisions in their life. They're beating themselves over the things in the past. What do you want to say to that person about how to really think about where they're at and how to shift their relationship with themselves?

Ocean Vuong (00:18:19):

Yeah. For me, it, as a, as a writer, it all begins with language. You know, often when we talk to each other, we use fluff language to get by. You know, oh, how's the weather? How about them patriots? You know, what's going on? How so and so? And and sometimes we don't answer that question. We say, yes, but it's, it's just a, a muscle memory. How you doing? Great. Good. And I think giving yourself permission to break, to break the norm of hiding and using language to obfuscate and just say, I'm not okay. Or changing the question, when was the last time you felt joy? Now you are in a different linguistic space.

Mel Robbins (00:19:11):

Hmm.

Ocean Vuong (00:19:11):

And you realize that people actually really hunger for that, but they don't wanna burden you with that. And they don't, we don't have the words to open the doors. We only have the words to move outside the doors. And so when the words change, so disruptions in linguistic patterns, which is what poetry and novels do, right. Because they're disruptions. We don't pick up a novel to confirm what we know. We pick it up to learn something new in a way we're disrupting ourselves.

Mel Robbins (00:19:40):

Oh, that's so cool.

Ocean Vuong (00:19:42):

Yeah.

Mel Robbins (00:19:43):

I never even thought about that, but you're right. Because I didn't pick up the emperor of gladness because I thought I knew everything was in there.

Ocean Vuong (00:19:51):

Mm-hmm.

Mel Robbins (00:19:52):

I picked it up to be transported and to use your word, to disrupt my day-to-day life and open myself up to something different.

Ocean Vuong (00:20:01):

Yeah. Yeah.

Mel Robbins (00:20:02):

Is there some recommendation that you would have if you're trying to disrupt the language you use around yourself and you find yourself saying, I'm not enough, it's never gonna work out. I'm not good enough.

Ocean Vuong (00:20:18):

Yeah. Yeah. Well, my very rudimentary, um, practice when I was a young poet, and I still do this, is write, just copy down your favorite poems and your favorite texts because now you are in someone else's head. So I would do that with Fredericka Garcia Lorca, Tony Morrison, Mary Oliver, you know, and when I'm stuck and when, when my language is running my life and it's toxic, I'm, I can just take another poet and I would just open up the book, put in my journal and just copy and feel, you know, that's, that's the beautiful thing about language is that it's, it's the most democratic tool we have. Hmm. Because everyone can use it.

Mel Robbins (00:21:07):

I wanna make sure that as the person's listening to you or they're watching on YouTube, that I highlight this tool that you spoke about. And I wanna expand it a little. 'cause you gave us this offering that I think is really important to make sure the person as you're listening, that you really get that you could do this.

Ocean Vuong (00:21:29):

Yeah.

Mel Robbins (00:21:30):

You said that, you know, if you're really feeling a sense of shame or if you are using your own words against yourself, I am not good enough. I have failed. I will never amount to anything. I'm not smart. Whatever those words are that you beat yourself up with. You said one tool is that you would open up a line from one of your favorite poems, and then you would write that line and trace those letters, and you start to then basically borrow those words in order to override and to teach yourself a new language. And one of the things I wanna say that I think people do instinctually is a lot of people save quotes they see online.

Ocean Vuong (00:22:19):

Yeah.

Mel Robbins (00:22:19):

And that's another way to do exactly what you're talking about. That if you are stuck with really self-defeating language and you know, you're beating yourself up, if there are famous quotes, if there are lines from a book, if there is something that has lifted you up or you've saved in a little folder somewhere on your phone, you could do exactly what you just said, which is write that out every day. And as you're tracing the shape of those letters, really imagine that those are the words that you say to yourself.

Ocean Vuong (00:22:57):

Yeah. It's like secular prayer.

Mel Robbins (00:22:59):

Yes.

Ocean Vuong (00:23:00):

Right. It's a form of prayer that you choose. You get to curate a kind of bibliography or bible for yourself. Right. And that you don't have to be religious to do it. Um, and in fact, this is what the early monks did. They would trace and, and replicate psalms and, and the Bible by hand. Right. And so that was kind of a meditative practice. And, and also imagine visualization. Imagine the people around you, right. Using the, the, the lang even just saying that, I hope my sister has a good day. Recenters us because there's, in Buddhism, we have this idea. In Buddhist psychology, we have this idea called sequential thinking.

Mel Robbins (00:23:42):

What is that?

Ocean Vuong (00:23:43):

In Buddhist psychology, we do not believe that you actually feel two things at once. One can only hold one emotion at a time.

Mel Robbins (00:23:51):

Right?

Ocean Vuong (00:23:51):

So it's like holding a ball. If you're holding the ball of hatred and, and, and, and whether it's for others or self-hatred, the only way to have another thought is to put down that ball. You can't just grab another Right. You have to put down that ball and then hold something else. And in meditation practice, we usually do a check-in with ourselves. And often, particularly nowadays, I sit down and something in me said, this is gonna be a bad session. I can't do it. My knees hurt. My ankles hurt. There's too much going on in the world. That email is bothering me. I really gotta get back, you know, to that. There's so much. And it's all about, I'm holding my own suffering. And what we do in Buddhism is that we start to displace our suffering with other people's suffering. So we, we start to think about the people closest to us, and then we radiate outwards.

(00:24:44):

Oh, my brother's having a bad day today. I remember now he's really struggling. My, my, my brother works retail at a, a sporting goods store. And, you know, it's, it's wage work. You know, sometimes it's hard. People yell at him. It's, and he's, he, he goes, it's a very stressful job. And it's why I'm holding him. And all of a sudden it's really, I don't know why this is, but when we hold our suffering, we suffer more. When we hold someone else's suffering, we have compassion. It's a, it's amazing why I would love someone much smarter than I to figure that out. But that's always the case. It's, it's very hard to continue to suffer when you are holding someone else's suffering. 'cause if something like love starts to, to come out of that, and some days I can't do it, some days I'm like, I just don't have enough to go there.

(00:25:39):

And, but just even saying that word, the, the phrase, I hope, you know, the people in my community can find safety. I'm gonna work towards that. I'm gonna work towards securing their safety. And then you start to, all of a sudden you visualize what you can do, how you can volunteer, how you can help. And all of a sudden you remove from yourself. And when you come back, 'cause it's all cycle, you come back to yourself and you say, gosh, I, I don't know how to pick up that ball anymore. I see it, I see self, self-hatred. I see envy, I see bitterness, I see self-loathing. It's all there. But I can't really pick it up. Before it was stuck. It was glued to my palms. But for some reason, moving outward has cleansed. And now I can't pick it up if I wanted to.

Mel Robbins (00:26:40):

It's so effective. It's so simple. As you were talking and explaining this, I, I just did it

Ocean Vuong (00:26:49):

Say more.

Mel Robbins (00:26:49):

So my mom and dad just lost a very, very good friend.

Ocean Vuong (00:26:54):

Yeah.

Mel Robbins (00:26:55):

And it was very sudden and really tragic thing that happened. And the second you started talking about your sister, I thought, oh, you know, I hope my mom and dad are having an okay day today. I hope that they are surrounded by friends today. I hope that their heartache is, is getting the support. You know? And then I thought, oh, I, I, I need to call them as soon as we're done talking. And everything that was self-centered disappeared from my mind. And there was this big expansion that happened. And as you're listening or watching, I want you to think about somebody that you love, that you really do hope with all of your heart, that they are having a good day. That they are getting the support that they need. And if you, if you truly step into this invitation, I think you will feel exactly what ocean's talking about. That somehow there was something you were holding inside yourself, even in the subconscious. Yeah. But when you direct that attention and focus outward, something expands, enlightens inside of you.

Ocean Vuong (00:28:13):

'cause you can only hold one thing

Mel Robbins (00:28:15):

Because you can only hold one thing. You know, I wanna ask you a question. 'cause I loved your New York Times blockbuster bestselling, profound novel, the Emperor of gladness. And when I opened up the first page to chapter one, and I read the first sentence, I thought, if I ever meet Ocean, I wanna ask you about what this means. And the sentence is, the hardest thing in the world is to live only once. What does that mean?

Ocean Vuong (00:28:54):

You have to make a count. You know, what does it mean to live and owe something to the people you love? Your obligation to them, to your community, and to live with that kind of care? Because the other side of that is yolo. You know, you only live once. Enjoy it, smash it all. And look where it's gotten us ecological despair, corporate greed, plundering, our environment, our planet just for profit. That's a lot of Yolo. Another side of Yolo is that, well, if you only live once, how do you live in a generative way? Hmm. How do you live with care and consideration with the meditative practice you just did? You don't have to be among and sit there and go home and do chanting. You can, you can actually do it while listening to someone talk. Right.

Mel Robbins (00:29:47):

I wanna unpack this even deeper. The hardest thing in the world is to live only once. And you said to you, that means you have to make it count. And what I would love to hear you talk a little bit about, because I've never asked anybody this question, but as a professor, I bet you are witness front and center to this sense of pressure and urgency that is not only inside your students, but it is 1000% inside every character in your book.

Ocean Vuong (00:30:22):

Yeah.

Mel Robbins (00:30:23):

But this pressure that I think is almost universal to make something of yourself.

Ocean Vuong (00:30:31):

Yeah.

Mel Robbins (00:30:32):

To make your life count.

Ocean Vuong (00:30:33):

Yeah.

Mel Robbins (00:30:34):

And for somebody who's listening right now who heard you say, oh, well, you have to make it count.

Ocean Vuong (00:30:42):

Hmm.

Mel Robbins (00:30:44):

And they now feel like, but I'm not ocean. Like I, I'm still, I'm stagnant. I'm, I'm working in this restaurant job. I didn't expect I would be here. It doesn't feel like it's counting at all.

Ocean Vuong (00:30:56):

Yeah, yeah. Yeah.

Mel Robbins (00:30:57):

What would you say to the person that's in that space? Because I think the pressure you feel to want it to count is a really good sign.

Ocean Vuong (00:31:07):

Yeah. Yeah.

Mel Robbins (00:31:08):

Of this sense inside you.

Ocean Vuong (00:31:13):

Yeah. Yeah.

Mel Robbins (00:31:14):

That there is something more for you. Does that make sense?

Ocean Vuong (00:31:17):

Absolutely. Absolutely. And, and I think for me, there's, there's two, you know, there's the, there's what society counts.

Mel Robbins (00:31:25):

Hmm.

Ocean Vuong (00:31:26):

And often because we're, we don't know any better. We're, we're told that we are, it's almost like a download Society downloads the set of values into us. And then we say, well, I need to get a good job. I need to get out of here. Right. And that's why like this novel, there's no escape plot. These, these are working poor people. They remain so, but it doesn't mean that their lives are doomed. You know, I reject this idea that a, a, a story about down and out poor people are, is only valuable if they can escape it. Because there's plenty of films, plenty of novels about that. And I think as Americans, we fetishize rescue. I think there are more Americans rescued in American films than actual Americans. <laugh> like, you know, and, and, and, and yeah, it feels good to watch that movie. Oh gosh. They look, they rose out of it. And then there's the other, there's the other part. There's the, there's an alternative count, which is your obligation to yourself and your life and your community.

Mel Robbins (00:32:34):

Mm.

Ocean Vuong (00:32:34):

Regardless of what that means in the cv, in the social standards and what have you. And I think what I learned working in fast food and the tobacco farms growing up, and what I wrote about is that in those spaces, there's something really, really humbling and powerful is that if you walk into NYU where I now work, if you walk into a doctor's office, a dentist's office, a law office, everybody who's there worked and wanted to be there, they might not like their job fine. But they all deliberately work to get there. But the folks in the, in the fast food restaurant, they never wanna be there. That's not their final goal.

Mel Robbins (00:33:16):

Hmm.

Ocean Vuong (00:33:17):

They're, they are deferring something else. Right. What's so humbling and powerful about that is that everybody, you know, you see, you realize there's another dream.

(00:33:28):

And when you work enough hours, you, it becomes really, it looms large. And you start to really wanna find ways to find out that dream. You know, you, you know, you have these kind of probing conversations. What do you, what do you do af what do you do before this? What you do? What you, what are you doing after this? You doing a night class, all of a sudden these spaces open up in these restaurants and corporations that were not meant to be there. They're kind of subversive utterances. And so, to me, I think what I mean by the hardest thing in the world is to live only once is to, to live according to your values. Again, dignity and what you owe to yourself, your, your family, and your community, however that means to you. And wrestling yourself away from the standards of ultimate success or what have you.

(00:34:20):

You know, like I am lucky to be a successful author and a professor, um, but I live in New England still because nine of my family members still live there. They're all refugees. They came with me. I don't have enough generational wealth to liberate them from the working poor. So my family still work at Amazon warehouses, nail salons. Um, and I'm there, you know, I've had job offers, uh, in lovely places. Paris, Germany. I said, as soon as they come in, I said, there's no way. 'cause I gotta take my aunt to her, to her doctor's appointment. I gotta do her taxes. I have to help my cousin go into a psych ward once in a while. Right. So, and I, that's not a burden to me.

Mel Robbins (00:35:02):

Hmm.

Ocean Vuong (00:35:03):

And I, I wanna make that clear, you know, that's a privilege I get to, it's a privilege to be able to sacrifice. I I get to help them because when I was growing up, you needed your tooth extracted chaos. You know, you had to call a loan shark. You have to, we had to call a grocery, a local Vietnamese grocery store to borrow money from God knows who to don't ask, don't tell. Right. And just to get like little things done. And so it was like the end of the world when those things happen. And now I can, my every emergency my family has, I can take care of. And I'm, I'm proud of that. And to me, if that's what I'm done doing with my one life that I'm given, then I'm really, really proud of that. And I think having the courage to break away from the social expectations of K and then realigning what counts for you. Mm. Um, it's hard work though. It took me 20 years and I, like, I'm, this is still new to me. This is a new feeling. Right. I don't wanna folks to have this understanding that I just, like, I've always had this, like I'm developing it as we speak.

Mel Robbins (00:36:16):

What I'd love to have you do is if you could speak directly to the person who's really resonating. 'cause I know so many people will, and maybe they're in the job and they thought they'd only work at the restaurant for two or three years. They, they're just getting by and they're starting to feel that dream of a different life slipping away.

Ocean Vuong (00:36:42):

Mm-hmm.

Mel Robbins (00:36:42):

What do you want them to know?

Ocean Vuong (00:36:46):

I think for me, um, you, you have a myth of yourself. And, you know, my, the myth for myself was to be a business person because that's just what I thought more money was. So like, when I was 15, I thought I was working in a tobacco farm for cash. It made, it was no Uncle Sam, no taxation under the table. Nine 50 an hour. Way better than minimum wage, which is seven 15. And it was so interesting because we grew, we lived in HUD housing section eight. And my mother ca sat me down one day and said, son, you, I, I, I crunched the numbers and you need to get a job. You are about to be 16, but you gotta just work at McDonald's. So can you imagine like, what, what happened to like, American dream upward mobility? Do what you want, follow your destiny. Right. None of, I'm like, what? Excuse me, <laugh>. And she's like, no, no, no. Like you, you can't even be the manager. Like you need to just be minimum wage because if you make any more, we'll be kicked out and we won't be able to afford an apartment on the open market.

(00:37:59):

So upward mobility could harm, could render you homeless.

Mel Robbins (00:38:04):

Hmm.

Ocean Vuong (00:38:04):

And then it clicked. I said, oh, no wonder every other teenager in my neighborhood is a drug dealer. Because if you're a child to a single mom, and there were daughters and sons in, in that too. If you're a child to a single mother and you want to help her out to get a job, if you get too much money, you're gonna lose your housing. So what are you gonna do? Sell weed on the side, get cash, put it on the mattress. Mom pays the light bill with her checks, you'll take her to the grocery store.

(00:38:40):

And I have seen folks do that. And I don't condone drug drug dealers. I've seen folks do that and move out and move on and have, and stop that and have relatively economically successful lives. I've seen folks do that and end up in jail and die. So it's just a complete crapshoot, you know? And so I, I went into the, the farm, you know, as a way to, to help my mother. But I had this myth that I would go out and be the one who has a degree. I was gonna study international marketing and really be the superhero of my family. And then I got to the school in New York to study, and I, I studied for just four weeks before I dropped out. And all that myth of who I am to myself crumbled. And I often say this, and not in any tongue in cheek way.

(00:39:40):

I said I became a writer out of failure. And more so I became a writer out of shame. I could have went home to my mom and said, mom, I tried. I can't do it. I'm not cut out to go to Chase JP Morgan. Like all my co colleagues are with their suits. I don't have a suit. We have one suit, it's called a funeral suit. That's all I had. I didn't even bring it. I was optimistic going to New York. I said, I'm not gonna bring my funeral suit <laugh>. I had, I went to enough funerals. So that's all I had, you know, and I didn't even conceive that you had to wear a suit for an internship. So I was so out of place that I just, I felt like a fool and I didn't have the wisdom I had Now. I was, I couldn't show up to that place and, and just see how much of an outsider I was. So I dropped out and I roamed the streets, couch surfing, doing open mics. And someone would say, why don't you, why don't you just go home? And if I went home, my mom would say, sit on down. I save you a seat at the nail salon. Pick up the filer, let's get to work. But I didn't do that 'cause I was too ashamed to go to her and say, I failed you.

Mel Robbins (00:40:51):

Hmm.

Ocean Vuong (00:40:52):

I'm the only one that knows English. I'm the only one that can read. I'm the only one that could potentially have a college degree and I'm gonna come back empty handed. I could not live with myself. So I stayed in the city. I stayed in Penn Station for two weeks trying to figure things out.

Mel Robbins (00:41:06):

Meaning you actually slept in Penn Station?

Ocean Vuong (00:41:08):

Penn Station. Yeah. Right under Madison Square Garden. It was the warmest place. Um, but Penn Station is open 24 hours and you can stay near the Long Island Railroad. And, you know, eventually I became a, a student, uh, at Brooklyn College. And I pursued a degree in literature, but it was because I was too ashamed. I would prefer to be homeless than go home and say, ma, all your dreams. 'cause I knew she had, I knew, even though she said, don't worry about it. I knew she had dreams for me. I couldn't face her and say, all that is over. So shame is a powerful thing. If, if you can transform your shame into action and, and then motivation, it could be the foundation for you to alter your sense of self.

Mel Robbins (00:41:58):

What would you say to a student that came to your office hours? And you know, professor Vaughn, I am so full of shame. I do not belong here. I have really screwed up. And the shame is not motivating them in a positive direction. It is drilling them into a hold.

Ocean Vuong (00:42:24):

Yeah.

Mel Robbins (00:42:25):

So if you had a student sitting in your office hours who was really pummeling themselves with shame, what would you say to them?

Ocean Vuong (00:42:36):

Um, every semester,

Mel Robbins (00:42:38):

Every semester this happens?

Ocean Vuong (00:42:39):

Oh my goodness. Especially in the creative arts. We have students who come from all over the world. You know, some of the most exciting work in Anglo phonic literature right now is coming out of India and Nigeria. And I have a lot of students from India, Nigeria. And boy, you know, imposter syndrome runs very, very deep. And here they are in NYU, they're, they're following their dreams. Meanwhile, these are the, these are the, the, the student, the most successful ones, they're, they're like ticking the boxes of their dreams. You know, they're not dropping out that nothing has gone awry. And they still feel this. And I relate to that immensely.

Mel Robbins (00:43:17):

Hmm.

Ocean Vuong (00:43:17):

So for me, I told them, I said, look, I share the same, the same shame and doubt that you do, but you believe, I have a sense that you believe that there is a kind of comfort and agreeability to being in the center of power. Right. In institution. That that's what people, normal people have. They, they, they don't feel like they're imposters. They feel like they belong here, that they should be here. But I tell them, I said, the day that I feel that I belong in institutional power is the day my creativity dies. I never wanna feel comfortable here. And we turn that into a pathology. We say, you are ill, you have a syndrome. But I refuse to believe that to me, it's an immune system. I have imposter immune system.

Mel Robbins (00:44:18):

What does that mean? Imposter immune system.

Ocean Vuong (00:44:20):

It means that when I'm in the center, I don't believe that being in the center alone is anything valuable or dignified. You have to still have conduct, you still have to have, uh, behavior and ethics. And also that when you realize, you, you go into these spaces and you realize, actually what I learned back there in my hometown that I thought I was escaping from was much more useful for me than what I'm seeing here. That the charade right of, of power and belonging is truly a hallucination. It was, there's people who feel comfortable here because they have been given this path. Their parents gave them this path, their grandparents gave them this path that they were following a trajectory that was carved for them. So of course they feel like they belong. But do you really want that? Do you want that path for yourself? Because that's also the denial of your own creativity. You need that kind of friction, that vigilance.

Mel Robbins (00:45:26):

Well, I, I think what you're, you're getting at is applicable to anybody.

Ocean Vuong (00:45:32):

Yeah.

Mel Robbins (00:45:32):

Because let's say you get a divorce. Yeah. And now you're single and your friend group disappears. And as you start to insert yourself into other social groups or you seal old friends, you will feel that separateness and you will feel that sense of, I don't belong here. And if I listen very closely, what you're saying is that that separateness and that friction is a very important and necessary ingredient to you being able to do the work to grow into or to be the person you're supposed to be.

Ocean Vuong (00:46:13):

Yeah.

Mel Robbins (00:46:13):

Whether it's the friendships you've outgrown or the places that you are never gonna quite feel like you belong in, or the work you need to do to build the skills so that you don't even think about it anymore because you now have the skills to belong.

Ocean Vuong (00:46:29):

Yeah.

Mel Robbins (00:46:29):

And so I think it's applicable to all of us. I'm wondering if there's one thing that you would recommend to begin seeing the beauty in your life, even if you're really struggling right now, especially if they've des they've related to a lot of the various things that you've gone through. What would the one step forward you would want somebody to take?

Ocean Vuong (00:46:55):

At the end of my semester, in every class I have my students do something very simple and I do it as well. And it's, it's, it's, you'd be surprised that many of them have never done it. Um, and I, I, what I do is I tell them, think about your intention. Why are you here? Why did you sacrifice so much? And I tell 'em, go back to that person that first found this art. The person who read a poem and said, just like Emily Dickinson said, my head is taken off. Right. And then decided that they wanna do that for other people. Write a work that transforms and affects people's life that way. Maybe it was just two years ago, maybe it was 10 years ago, maybe they were just seven or 20. Go back, find that person and collaborate with that person. Bring that person into the room.

(00:47:57):

'cause often in our linear progress in professional life, we often think our older self is not smart enough, naive, leave them, leave them back there. But bringing that person in the room and asking that person, how were you so strong? And how was that intention so powerful that you didn't even know how to get here? You didn't know how to get to NYU, but you sent me, you, my younger self sent me here. Like that little pebble in the pond. I am the ripple. You are the pebble. I'm the ripple that have come from you. So I need you, when I am inundated by the pressure, when I'm asking, why am I doing this? What is it for? What's the point? Why am I in this rat race when I'm about to give up, when I'm fading, I am gonna, I need to bring. So I tell them every time you write, every morning you wake up, bring that person, have them sit right next.

(00:48:59):

'cause they know more than you do. They got you here without even knowing what a professor is, without knowing what the New Yorker is, without knowing what a, you know what a c curriculum vitae is, right? They just had that boom. And you are on the journey. They set. So what you need to do is say thank you to that person. So at the end of the class, I tell all my students, at a count of three, you say thank you to yourself aloud. And you need to say that every day because no one else is gonna say that for you for this journey. So we close and we hope 1, 2, 3. Thank you. Thank you Ocean. And it's an amazing thing. Thank you Ocean. Thank you Mel saying that to yourself.

Mel Robbins (00:49:52):

I am the ripple. You are the pebble. I felt this huge chill when you said that this idea that your younger self was the pebble. Yeah. That had an intention, whether your present or not to it. That set in motion, this ripple that created the you that you are today. If the person listening does not know what their intention is, they do not know what age or what scene their life that pebble was cast, is there anything that they can do that could help them find that center of intention to begin with?

Ocean Vuong (00:50:44):

I think paying attention to the world and yourself, and again, seeing what you owe eventually. Atte, you know, Simone ve says, the most generous thing we can ever give is attention. And I think paying attention to the world, often we think it's about giving attention, but in fact, we are also discovering ourselves when we look carefully at the world. And I never knew I was gonna be, you know, when I was growing up, it was factory worker, nail salon, um, the army Job corps, right. Or long haul trucker. Those were the things, or jail. Right. Those were the things that was available and what was happening around me. And, and so I, I never, no one ever said, you can be a professor. In fact, I didn't even know poets were something you, you could become, I thought it was like preordained by the government.

(00:51:46):

I thought like the president signs like a, a a list. You get in the mail and you say you get to be a poet. Then they give you a cabin in Vermont, you go there, you scribble away, then you send your piles of paper to Barnes and Noble <laugh>, and they go out in the back, they make a book and they wheel out a cart of books. How would, how else would it happen? <laugh>. And so the idea that one could be a poet is a complete journey of failure, of objection of shame. And so I'm 37, half of my life have been in a, in nowhere land. Absolute loss, absolute objection. And I could, I would never have told you that I was gonna be a professor or write books. You know, I, to me, I am miraculously in the whipped cream of my life. And I've been in it for 20 years. I, I've been able to do what I love, but it was not a life that I thought I could afford in any sense of the word.

Mel Robbins (00:52:48):

So the pebble, if I'm really like, I just felt like I should say the pebble is though that deep intention buried within you.

Ocean Vuong (00:52:59):

Yeah.

Mel Robbins (00:52:59):

To be in the whipped cream of your life.

Ocean Vuong (00:53:01):

Yeah.

Mel Robbins (00:53:01):

To know the truth. That there is something that is meant for you. That there is power, that there's dignity, that there's beauty, and this sense that you were gonna figure it out.

Ocean Vuong (00:53:19):

And it was something much more materially fundamental in that I wanted to take care of my family. Hmm.

(00:53:28):

I knew I was the only one. I looked, you know, I looked long and hard at their life. And I said, all right, they've been in the factories. I mean, I went back to that moment with me, me and me and my mom at her bedside when I was 10. And when she said, I'm sorry, we're so stupid. That was the pebble. I didn't know it then. That was my, so it wasn't be a poet. I say that to my students that we're in poetry class. Right. It gets too existential beyond that. Right. But for me, that was the pebble. It was whatever I was gonna do to take care of my mother and my brother and my aunts. That was what I was gonna do. And when I realized that I could take care of my mother and be an academic and a poet, then that was when it was like seventh gear. I, I became kind of ruthless in my pursuit of my craft because I knew it was something that would then support my family. That was my motivation. So now I say, oh, I, I, I was given that my objection was a motivating factor. Without them, I don't think I would've worked as hard. I would not work as hard for myself. I'll tell you that Mel, I, I would not study as hard, I would not read as much books. I would not write as many drafts without the pressure knowing that they really depended on me to get them a better life.

Mel Robbins (00:55:05):

Thank you for sharing that, because it was so helpful to see that your pebble actually wasn't this epiphany, I wanna be an artist or a poet. That your pebble was something so much more deeply connected to your value Yeah. Of taking care of your family. And that shifted for me, the way I think about I am the ripple and my former self is the pebble, the intention is the power. And it's there. And I really, I got a lot out of that story.

Ocean Vuong (00:55:46):

Thank you.

Mel Robbins (00:55:47):

Thank you. So, you know, one of the things I was also curious about, because you've been a, a professor for 11 years now.

Ocean Vuong (00:55:52):

Yeah.

Mel Robbins (00:55:53):

What is the thing that's really holding your students back more than anything right now, from being themselves?

Ocean Vuong (00:56:02):

The fear of humiliation. Um, we call it cringe culture. We can call it, you know, um, fear, authorial, hesitation, whatever you wanna call it. I've had the great luxury of being a professor only to Gen Z. My entire career has been educating Gen Z. From the very oldest now to the very youngest. I've watched this generation grow. And I've watched the, um, the, the horrible public, um, precarity that they have to navigate. You know, when I was a kid in the nineties, you do something silly and your class makes fun of you. Worst case your school makes fun of you. And then after summer break, all is forgotten, right? <laugh>. And then you, you, you kind of cleanse by the amnesia of summertime. But now you do something out of the norm as much many children are inclined to do. Your, your kids, your brain is developing.

Mel Robbins (00:57:06):

Yeah.

Ocean Vuong (00:57:07):

You can be filmed without your permission. And a week later, an entire country that you have never stepped into is laughing at you. And then years later, you become a meme, a symbol that is completely extracted from your personhood. So the meme is one of the most brutal realities of our 21st century mode of communication because it transforms a human being with a historical life and a personality into a communication object, into a sign which now serves somebody in a group chat. So by the time I get them, I teach a graduate program. So they're 22, 23, and we get the ones who have already committed themselves to our practice. So we get the ones that are kind of professionalizing. But without fail every year at the first day of class, you can see by the body language in the room how deeply beaten down and afraid my students are for being a poet. So I tell them that the classroom is a laboratory of failure. This is a place to fail. This is a place to be embarrassed. And I'm, I'm not going to critique you for the first few weeks, and we're not gonna critique each other. We are a culture obsessed with, with static truths. We have an a word for a bud and then ro a word for rose. Rosebud rose.

(00:58:56):

But there are infinite moments in between. You know, there's a moment where the, the rose just starts to tear. And if you've zoomed in enough, you don't even know what you're looking at. It's still a part of it. But we don't have a word for that.

Mel Robbins (00:59:11):

Hmm.

Ocean Vuong (00:59:12):

And, and to me, so much of life actually exists in this liminal, monstrous, undefinable space in between the two definitions of rosebud and rose. And so I tell them, I said, you are now in the space between the rosebud and the rose. That's what these 14 weeks are. We don't have a word for that. Sorry. Doesn't matter though. So normalizing the idea of failure as a necessary procedure of growing as a human being and not using judgment as a punishing tool of progress. What a lot of students want from the, from the classroom is a factory. They've been taught that, uh, I'm gonna go to NYU I'm gonna feed my weak poems into the NYU factory and a professor and my peers are going to, to fix everything. Right? It's all about this false idea that if I just keep working a finished brand new, you know, T model Ford poem will come out at the end of it. And it's so completely false fantasy. So it's introducing to them the, the larger reality that all of this will come through error and errancy. But in fact, error and errancy is part of being alive. And not only that, but part of innovation. That's the daring Daringness. And when I set that up as the re re elaborate that as the, what the classroom is for, you see the body language change. Hmm. You know, and, and, and I'm like, oh, there you are. There you are.

Mel Robbins (01:00:51):

What I love so much about your work and about the way that you think and the way that you talk about your experience is you have this unique ability to dig deep into these subtle moments in people's lives. And I, I feel like you've got this ability to really normalize what is a experience that so many people feel, but don't have the words to describe and the message that your work carries in. It is the opportunity for all of us to not only create that space for ourselves wherever you are right now. 'cause being in a, in a moment in your life where shit is still and you don't feel like it's going anywhere.

Ocean Vuong (01:01:41):

Yeah.

Mel Robbins (01:01:42):

And you are feeling like this is really what it's going to be. Am I really making my life count? Especially as you get older?

Ocean Vuong (01:01:56):

Yeah.

Mel Robbins (01:01:58):

I think everybody's had that experience.

Ocean Vuong (01:02:00):

And imagine being raised by someone like that. Imagine being surrounded and, and multiply. If you're in a community like that or a family, everything you said multiplied by eight or nine, everyone around you feels the same way. Right. And the, the, the, the deep resentment, the deep, um, sadness. Uh, but also like,

Ocean Vuong (01:02:24):

Again, like my stepdad worked at Stanine, he worked at a place called Stanine. He made a screw his whole life for like 30 years. He made the screw that went into gas pumps and that company shut down. It went overseas. So he's uneducated refugee from Vietnam, spent seven days in a boat and went to a refugee camp, then came to Hartford, met my mother, and he spent 30 years making a screw. And now he doesn't make a screw anymore. What does he do? You know? So he goes to work at Cult, which is a gun factory in, in also in Connecticut, Newington.

(01:03:07):

And he makes a smaller screw that goes into the cult magnum and gas pumps and guns is the most quintessential American story. Every day after work, he hung up his uniform in our living room on a thumb tack because we, we didn't own it. So we could not put anything on the walls. We couldn't paint it. We had to get permission. It's a bureaucratic nightmare just to paint your walls. He hung his, his his shirt there because on the right chest it said Ngoc, NGOC, his name with the DCR stitched in beautiful blue thread. And every time someone come over, he would point to it. I said, I work at standardized. I have healthcare. That's how low the bar was. Right. It's like, and we're still feeling that bar. It's a big thing to say, I have healthcare. It's a big thing to say, I have a salary.

(01:04:04):

It's a big thing to say, I am, I belong to a place with a uniform. They believe in me enough to gimme a uniform with my name on it. I looked at that for years similar to how you described your family in the farm. And I saw that and I told myself, that can't be my American life. This man works from 3:00 PM to 12:00 AM I never see him. I look into his room, I see a tough black hair out of his blanket. That can't be me. But if you asked him, how did you spend your American life? He's retired now. He would've said, that is his absolute triumph.

Mel Robbins (01:04:44):

Hmm.

Ocean Vuong (01:04:46):

That was he, he lucked out. Right? He would tell us this. He said, I, he would convince me to go work. And he said, gosh, it's, it's amazing. This is it. Not everybody. And wasn't wrong. He was not wrong. So I, I think that's why I wrote this book because I think everyone around me wanted stories about poor people who got out of their situation so that the reader feels good. I, I just was not interested in writing a where like, to make rich people feel good about poor people. Right. Or, you know, it, it's all worth it. Or creating poverty porn to build sympathy. I say, no, this is just American life. And in fact, we want the story of escape. Our history books are filled with stories of escape, of revolutions, of people who overthrew things. But history itself is predominantly people who are stuck.

Mel Robbins (01:05:44):

Yeah.

Ocean Vuong (01:05:44):

Stuck in marriages. They never wanna be in stuck in wars. They did not choose to fight in, stuck in coal mines. Right. They never thought they'd be in. And some of them, you know, stuck in lives they never chose. None of us are chosen to be born, but we stay, we stay around because we realize there's love here. That's what I'm interested in. None of us chose to be here. None of my characters chose to be here. But they stay because they discover love.

Mel Robbins (01:06:12):

Hmm.

Ocean Vuong (01:06:13):

And it doesn't make poverty better. It doesn't make it even tolerable, but it gives your life a kind of significance when you realize that you are you, if nothing else, if nothing else, nothing improves. Which for the most part in this book, spoiler alert, nothing much does. You are still capable of giving and receiving love. And that's no small thing. It, to me, it's a, it's a huge, significant part of one's life. Especially after watching my mother die. You know, when, when she was, we knew it was terminal. She spent months bedridden breast cancer, most likely from all the chemicals she breathed, it has eaten into her spine, stage four metastatic into her brain. You know, she, from diagnosis to death was seven months. And when I asked her, well, what do you want? What do you need? What was your life? She just told me the smallest moments. Oh, you remember when we used to to go get chicken nuggets after work and we sit in the parking lot. That was nice. I didn't even remember that. That's completely her memory. Then when she said it, I said, oh yeah, gosh, I haven't thought about it all this time. And I couldn't believe she held that it was such, um, an edifying moment. 2019. I started this book in 2020,

Mel Robbins (01:07:52):

Hmm.

Ocean Vuong (01:07:53):

Seven weeks after she died. And I thought, oh gosh, it's not about the big things. It's not, it's about eating fricking chicken nuggets in a McDonald's parking lot with your son. And I thought, if, if I am a, a writer worthy of my salt, I have to use what I've learned and my skill and talent to hold that. Let me, if nothing else in, in my one life, the hardest thing is to live only was let me use what I've developed all these decades to make that shareable with a reader because I just wasn't seeing it in the media that I was told I should consume.

Mel Robbins (01:08:46):

Well, it absolutely comes through. Thank you. It absolutely comes through. And, you know, it reminded me of, of a lot of periods in my life where I was rushing through it, hoping to get somewhere else and, you know, help me slow down and like really reflect on what was right there.

Ocean Vuong (01:09:10):

And sometimes you need the other person to say it 'cause you don't know.

Mel Robbins (01:09:15):

Yes.

Ocean Vuong (01:09:16):

And how incredible if, if my only like contribution to your beautiful podcast is just to get people to change the way they say hello. That would be amazing. You pick up a phone and instead of saying, hi, how are you? Good. Good, good. Just say, Hey, what's the last thing that made you joyful? I wish I knew that a lot sooner. I would have very different conversations with my mother and, and the friends I lost, you know, to the overdoses and suicide. I, I would, I would do it all over. But, you know, you learn things so, so slow. But every time we pick up the phone, we have the opportunity to switch the gears.

Mel Robbins (01:09:58):

Right.

Ocean Vuong (01:09:58):

It's always in our hands because we're just holding one at a time, one feeling at a time.

Mel Robbins (01:10:04):

Well, I also think that this is an enormous invitation to ask yourself that question. When was the last time that you felt joyful?

Ocean Vuong (01:10:16):

Um, so I, I play in a queer basketball league with my brother.

Mel Robbins (01:10:22):

I'm trying to imagine that by the way, <laugh>.

Ocean Vuong (01:10:26):

Um, yeah. It could be hard. It's hard for me to imagine until I'm there. And I was like,

Mel Robbins (01:10:32):

Well, I immediately went to costumes and of course, and I was thinking of the scene in the book, which is one of my favorite scenes, where one of the characters, BJ has this dream of becoming a regional champion in wrestling.

Ocean Vuong (01:10:46):

Yeah.

Mel Robbins (01:10:46):

And everybody piles into a car and goes to her match and things go horribly. <laugh>. Yeah. Awry. Yeah. But you feel the love of friendship

Ocean Vuong (01:10:57):

Yeah.

Mel Robbins (01:10:57):

As they surround her in this moment where she's basically humiliated.

Ocean Vuong (01:11:02):

Yeah. Yeah.

Mel Robbins (01:11:03):

And so I thought of costumes and the energy. Yeah. And it's very similar. Yeah. Well, hopefully not a lot of humiliation.

Ocean Vuong (01:11:12):

Oh, well, depends, depends. Um, you know, joyful humiliation, there's a, you know, the, the, the body humbles you, especially at 37. Um, but I, I play in this league with my brother and I always feel so much joy because I never thought that you could participate in a very competitive, historically very competitive cutthroat. Like in, in my, I grew up with like street ball, AND1 one mixtapes skateboarding culture. And it was like, it was beautiful, but it was also like filled with hyper masculine aggression and toxicity and being in a queer, and when I say queer, I mean like, you know, all genders, all bodies, all experiences, all hair colors. Like hats bring it like co like you, you're, you're on it. You, you got the right image. Like it's, you know, we look like a beautiful athletic carnival. And it's amazing. And I look forward to it every Sunday,

Mel Robbins (01:12:14):

A beautiful athletic carnival <laugh>. That is a mouthful of amazingness. That's all I'm gonna say.

Ocean Vuong (01:12:21):

Yeah. Tell that to the NBA, you know. Um, but, but just moving my body next to my, my brother, I felt, um, so much joy. And I think it's, I'm proud of him. You know, I think he's the one that I go to first. Um, when I do that, meditation is my brother. Okay. You know, he's always, we're 10 years apart. Um, so I, I'm like a weird gay brother, father, you know? Um, but it, you, you embrace it. You, you don't, it's not a nuclear family. What's a nuclear family? It's just family. It's what you owe to me. Like that's, this book is about who owes who, what. And I what do these characters do for each other? They, they pile into a van off the clock and they go watch their manager wrestle at a bar to catastrophic, you know, results. And then they say, you're still our manager, <laugh>. Because that's what I witnessed. You know? And that's what we remember. You know, if we're lucky, if we are so lucky, we will get a deathbed. A lot of people don't get a deathbed. Hmm. And when we get that deathbed, we will remember these moments when people were kind to us, when they offered us grace and attention. And I wanted to just, what a miracle to have the technology of the sentence, put that in a book and then just throw it in the world and say, do you get it? Do you get where I'm coming from? And then unbeknownst to me, so many people saying, me too.

Mel Robbins (01:14:02):

So do you think the thing that you owe one another is kindness and grace and attention

Ocean Vuong (01:14:13):

All, all three. Kindness, grace, and attention. Absolutely. Because kindness is thrown around a lot. Right? It's like, oh, be kind. Be kind. But what I love about it, I love kindness even more than the other word that gets trafficked a lot, which is empathy. Because empathy can still be static in a lot, in a, in a way it could also be dangerous and let render us complacent. To me, kindness is such a, a powerful testament to what it means for us to act on our debt to each other.

(01:14:54):

Kindness is now empathy via action. And a lot of times growing up, we knew there was, we're not gonna get anything back right away. 'cause we couldn't, you know, the characters in this book don't have anything to really give each other, but each other, you know, there was a line from, I believe it's the Bible I read, I, it's a religious text. I don't know if it's, um, the work of St. Augustine or the Bible where the, the line was we are given ourselves. That is the gift of life is that we, we get our, we are given thisness and I, you know, I I I'm not a Christian, but I really love that idea that, that, oh, I'm taught by this country that I'm out. I need more, I need to go out and grab more. But thisness business myself was already this invaluable gift. And then to then gift myself to others through service and kindness.

Mel Robbins (01:15:58):

I, I, I love that statement given to ourselves because, you know, a lot of people are searching for purpose. And I've always thought purpose is when you recognize that you've been given to yourself.

Ocean Vuong (01:16:14):

Yeah.

Mel Robbins (01:16:15):

But your purpose is then to give yourself to other people in service, in kindness, to give other people the dignity and grace that you have to give.

Ocean Vuong (01:16:32):

Yeah. Empathy as an end game is a trap. It's about how it can be put into action.

Mel Robbins (01:16:39):

Yeah.

Ocean Vuong (01:16:39):

Empathy is a procedure into the solution that we all really hope for.

Mel Robbins (01:16:46):

You have shared so much today, and one of the things that I would love to ask you is for the person who's listening, who wants to build a meaningful life, one that has room for joy, for connection, for dignity, for grace, what do you hope they take from this conversation today and from your work?

Ocean Vuong (01:17:15):

I hope, I, I hope people realize that if they don't already, that a meaningful life is not a life that you use to prove to yourself or others that you are valuable. A meaningful life is finding the power and the value where you are. And, and I say this and I know for some it might sound like a bunch of, you know, hullabaloo. But I, I say this as someone who, if, if nothing else, I'm someone who have trespassed these class layers by no plan of my own. You know, I came, I went from the projects as a refugee, and now I'm in billionaires mansions begging for funding for my students. So now I see a whole different world. And I say this because I think it's easy to, to fall into the trap of, oh, my achievements are me. They're just what I do. Right. And to me, it's like you are told that you gotta go up, go up the mountain and there'll be a light that will heal everything. And that's what you're told as a little kid. And it's interesting because like being from the working poor, we, we were so naive. Our parents were so naive about education and professionalization. 'cause they were never part of it.

Mel Robbins (01:18:56):

Hmm.

Ocean Vuong (01:18:56):

So they thought it was a panacea. They actually gave it more credence than it deserves.

Mel Robbins (01:19:01):

That I can just get you there. The there will take you,

Ocean Vuong (01:19:05):

It'll take care of itself. And little did they know that there's nepotism, greed, payoff, nefarious shenanigans. And in a way it was just another wasteland. And that's been my experience. You go up the mountain and then there's a plateau, and then there's an award ceremony. And then you look around and say, oh gosh, there's a lot of skeletons here. It's just smoldering. And then they said, whoa, whoa. No, no, there's another one, another level. Right This way keep on working. And you get up that one, you say, okay, maybe, maybe I'll see things differently from up there. And you get up to that platform, you say, oh my gosh, it's ano it's a graveyard. There's just, there's bitterness, envy, jealousy, hatred, pettiness, everything. I thought I was escaping down there. It's still here, but at least, but even here, there's nowhere else to go. You know, it's either you go up or you get pushed off. Right. And eventually I realized that it wasn't about going all the way up. It's about using that as a way to build a life for yourself and then coming back down.

Mel Robbins (01:20:24):

Hmm.

Ocean Vuong (01:20:26):

How do you come back down from the mountain? My whole life changed in the past five years realizing that, 'cause I'm like any American, I was told, go on, move on up. Go, go, go, go get 'em, get 'em one award. Great. That will launch you. You know, like these are strategic that you get an award now you can apply to a, a tenure track job.

Mel Robbins (01:20:45):

Yeah.

Ocean Vuong (01:20:46):

Then you, then you have to do service. You go to your deans, you look at all the awards I got, can I get a raise? You know, then can I get a load off my teaching so I could do research? Can I get research fun? So all these strategic, they're not nothing. But then eventually you look around, you said, when is it gonna end? And now I, I realize if I don't come off this mountain and find my people, my brother, my aunts, my family, I'm gonna be in, I'm gonna be buried up there.

Mel Robbins (01:21:12):

Hmm.

Ocean Vuong (01:21:15):

And that was the most liberating thing. You can go into these spaces now. And I say I don't belong here, but I have work to do here.

Mel Robbins (01:21:24):

I love the visual and the metaphor of coming down the mountain.

Ocean Vuong (01:21:30):

Yeah.

Mel Robbins (01:21:30):

Because for me, it feels like grounding back into ourselves.

Ocean Vuong (01:21:36):

Mm.

Mel Robbins (01:21:37):

And into the things that are truly meaningful that we take for granted into the beauty that is right in front of your life. Instead of thinking that more of anything other than what you said, if you have safety and if you can pay your bills and you have something that you can wake up and do, that adds a little value to your life. Even if that means you wake up and you drive your grandmother to her doctor's appointment, then where you are, you have enough. And if you can start there, you actually are grounded into your values and that's where your power is because you know who you are when you can do that. So I love the metaphor of like, dropping down.

Ocean Vuong (01:22:26):

Do you feel that's where you are now?

Mel Robbins (01:22:28):

Oh, a hundred percent.

Ocean Vuong (01:22:28):

Yeah.

Mel Robbins (01:22:29):

A hundred percent. Yeah. Like everybody always asks me, oh my gosh, you know, the book and the podcast and the this, and you know what's more? And I'm like more, yeah. Like, I have more than I ever thought I would ever have. I want more time. I wanna be present with the people I love. My parents are getting older, I'd like to spend more time with them, and they don't live near me. I, I i I am more certain of what's important in life because all the things that you see right now happened after I almost lost everything. That was important.

Ocean Vuong (01:23:05):

Yeah.

Mel Robbins (01:23:06):

And you don't forget what it's like to roll two tomatoes back across a dirty grocery store conveyor belt. And you don't forget what it's like to think that your family's about to be torn apart or you're about to lose the house or whatever. And so i, I am more certain of who I am and what matters. And that gift that you have been given ourselves during this lifetime, that it's the most powerful place you could possibly be. And so I, I got so much out of your, your book. I have loved meeting you and talking to you and Ocean Vuong, what are your parting words?

Ocean Vuong (01:23:56):

You should try to, to scare yourself, but don't be scared of yourself.

Mel Robbins (01:24:04):

Hmm.

Ocean Vuong (01:24:05):

It's important to scare yourself. It's okay to scare yourself, but don't be afraid of yourself. And I think we can talk a lot about ambition and craft, but the core of it is a daringness try risk. Don't be afraid to be humiliated, but don't be scared of yourself.

Mel Robbins (01:24:30):

Thank you.

Ocean Vuong (01:24:31):

Thank you.

Mel Robbins (01:24:32):

Thank you for your beautiful and life-changing work. Thank you for writing. Thank you for everything that you are doing to help us find joy. Even in those moments where we are deeply struggling, your work really matters. It's made a huge impact on me. And I know that our conversation today is going to make an enormous impact on the person who's listening right now and who they share it with.

Ocean Vuong (01:25:12):

I'm so, so honored. Thank you. I hope so too. Thank you so much.

Mel Robbins (01:25:16):

You're welcome. And I also wanna thank you. Thank you for taking the time to listen to our conversation today. Thank you for watching on YouTube. I am certain that you are as moved by what we discussed as I am. And I just wanted to tell you in case no one else tells you today, as your friend, I love you. I believe in you and I believe in your ability to create a better life. And I hope one of the things that you'll really take away from this is that you already have a beautiful life. You already have so much that you can be joyful about. You have so much that you can be thankful for. And when you hold space for that joy, when you hold grace for yourself, your life instantly becomes a little better exactly where you are.

(01:26:12):

All righty, I'll see you in the very next episode. I'll be waiting to welcome you in the moment you hit play. And thank you for watching all the way to the end. And thank you by the way, for hitting subscribe. If it's lit up right now, it means you're not a subscriber. My goal is to make sure 50% of the people that watch this channel are subscribers. It's free. I know you're the kind of person that loves supporting people who support you. And since you watched all the way to the end, I guarantee you this conversation about finding purpose and meaning, even when life is really hard was really an amazing support to you. So thanks for hitting subscribe and I know you're thinking, okay, Mel, what could I watch next? Because recommending something is how you can support me. You are gonna love this video next and I will be there to welcome you in the moment you hit play.

Guests Appearing in this Episode

Ocean Vuong

Ocean Vuong is a New York Times bestselling author and award-winning poet. He’s received major literary honors, including the American Book Award and the Mark Twain American Voice in Literature Award, and he teaches Modern Poetry and Poetics in NYU’s MFA program.

-

The Emperor of Gladness

Ocean Vuong returns with a big-hearted novel about chosen family, unexpected friendship, and the stories we tell ourselves in order to survive

One late summer evening in the post-industrial town of East Gladness, Connecticut, nineteen-year-old Hai stands on the edge of a bridge in pelting rain, ready to jump, when he hears someone shout across the river. The voice belongs to Grazina, an elderly widow succumbing to dementia, who convinces him to take another path. Bereft and out of options, he quickly becomes her caretaker. Over the course of the year, the unlikely pair develops a life-altering bond, one built on empathy, spiritual reckoning, and heartbreak, with the power to alter Hai’s relationship to himself, his family, and a community at the brink.